Biomaterials Translational ›› 2023, Vol. 4 ›› Issue (2): 115-127.doi: 10.12336/biomatertransl.2023.02.006

• RESEARCH ARTICLE • Previous Articles

Hanyu Chu ), Ying Bai

), Ying Bai )

)

Received:2023-06-04

Revised:2023-06-15

Accepted:2023-06-20

Online:2023-06-28

Published:2023-06-28

Contact:

Daping Quan, About author:Daping Quan, cesqdp@mail.sysu.edu.cn;

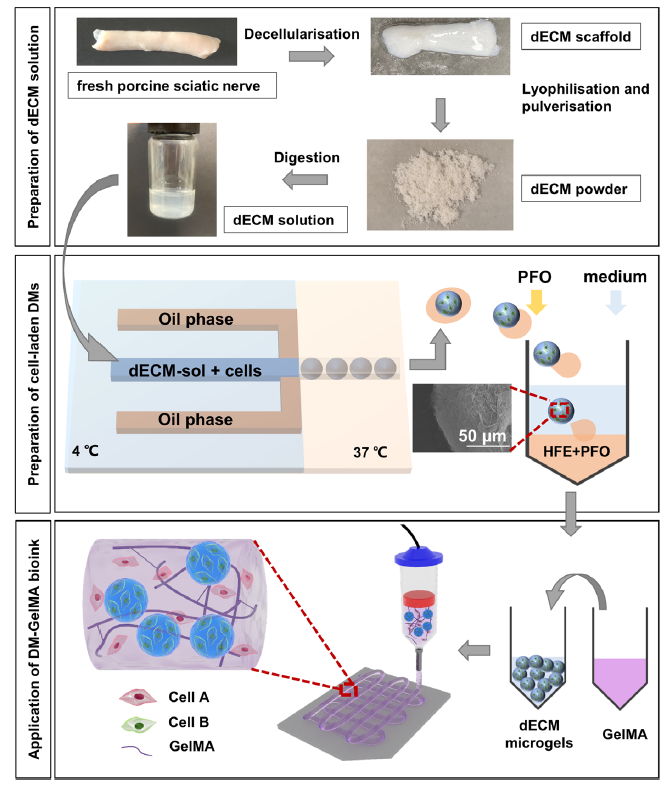

Figure 1. Schematic diagrams illustrate the preparation of the DM-GelMA bioink for extrusion-based bioprinting. The upper diagram shows the preparation of dECM solution. The middle diagram shows the temperature-controlled flow-focusing microfluidic device to prepare cell-laden DMs. The lower diagram shows the preparation of DM-GelMA composite bioink and its application in extrusion-based bioprinting. Created using 3D Max 2021. dECM: decellularised extracellular matrix; DM: decellularised extracellular matrix microgel; GelMA: gelatin methacryloyl; HFE: HFE: hexane, 3-ethoxy-1,1,1,2,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,6-d odecafluoro-2-(trifluoromethyl); PFO: 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluoro-1-octanol.

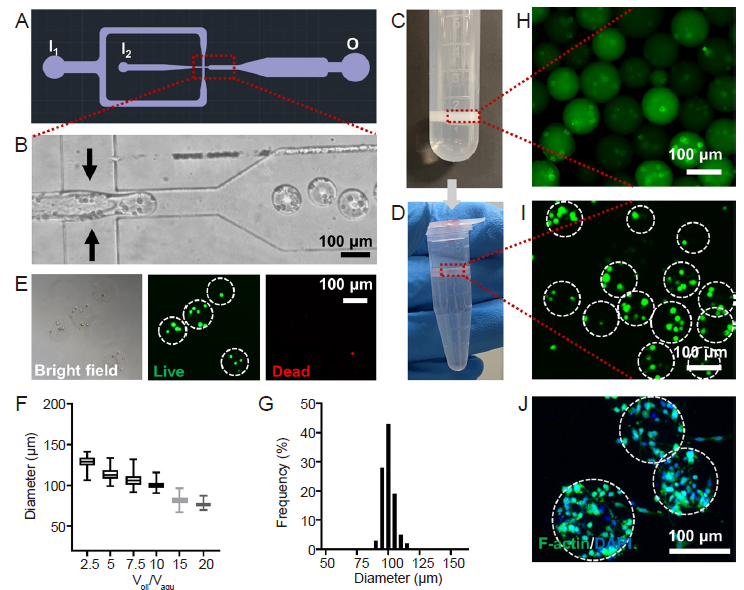

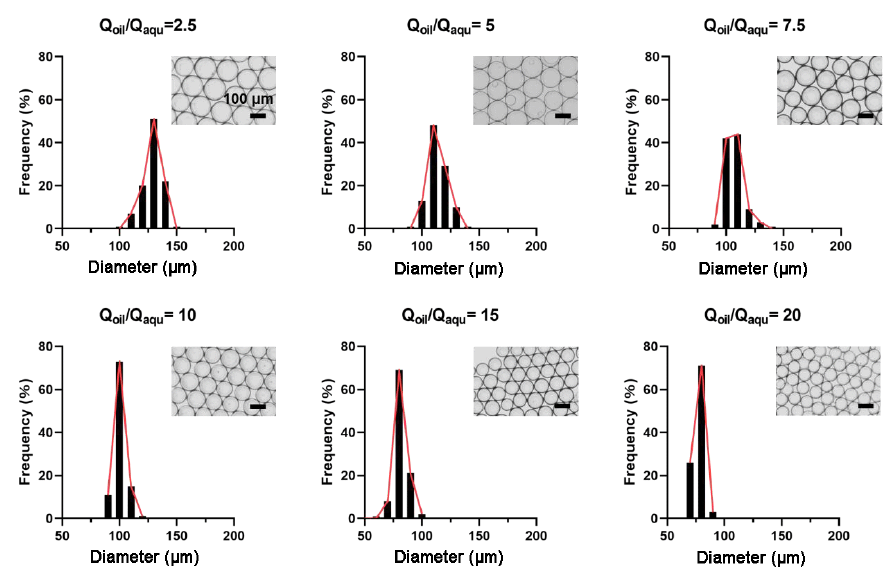

Figure 2. Preparation of the cell-laden DMs. (A) The design of the microfluidic device for high-throughput generation of microgels. Created using AutoCAD 2021. (B) Enlarged view of microfluidic chip during water-in-oil emulsification. (C, D) Photographs of DM collection after gelation (C) and PFO-based transfer into aqueous solution (D). (E) Live/dead staining showing the viability of cells encapsulated in the DMs, green: live cells, red: dead cells. (F) The diameters of the DMs were highly dependent on the flow rate ratio (Qoil/Qaqu) during emulsification. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. (G) Distribution of the DM diameters at Qoil/Qaqu = 10:1. Representative fluorescence micrographs showing the DMs containing the PC12 cells pre-labelled with Cell Tracker green fluorescent dye, when the DMs were dispersed in the (H) oil and (I) aqueous phases, respectively. (J) Fluorescence staining showed the cytoskeletal of PC12 cells encapsulated in the DMs, green: F-actin, blue: DAPI. The dashed lines circle out the DMs with pre-encapsulated PC12 cells. Scale bars: 100 μm. DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DMs: decellularised extracellular matrix microgels; PFO: 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluoro-1-octanol; Qoil: the flow rate of the oil phase; Qaqu: the flow rate of the aqueous phase.

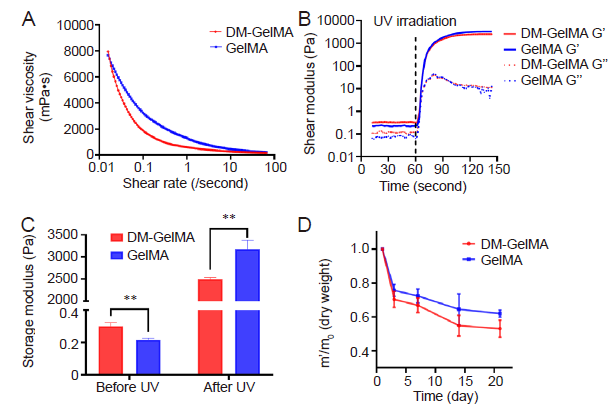

Figure 3. Rheological properties of the DM-GelMA composite hydrogel. (A) Rheology assessments showed shear-thinning behaviors evident in both DM-GelMA and GelMA hydrogels. (B) The shear moduli of both DM-GelMA and GelMA hydrogels, UV light was turned on 60 seconds after the rheology test had begun. G' (solid lines): storage modulus, G” (dashed lines): loss modulus. (C) Storage moduli of both DM-GelMA and GelMA hydrogels before and after UV photocrosslinking. Data are presented as means ± SD. **P < 0.01 (Student's t-test). (D) Degradation of both DM-GelMA and GelMA hydrogels presented as the ratio of residual mass during 3 weeks of PBS immersion. m0: the original dry mass, m': the mass of the lyophilised hydrogel at each time point. DM: decellularised extracellular matrix microgel; GelMA: gelatin methacryloyl; PBS: phosphate buffered saline; UV: ultraviolet.

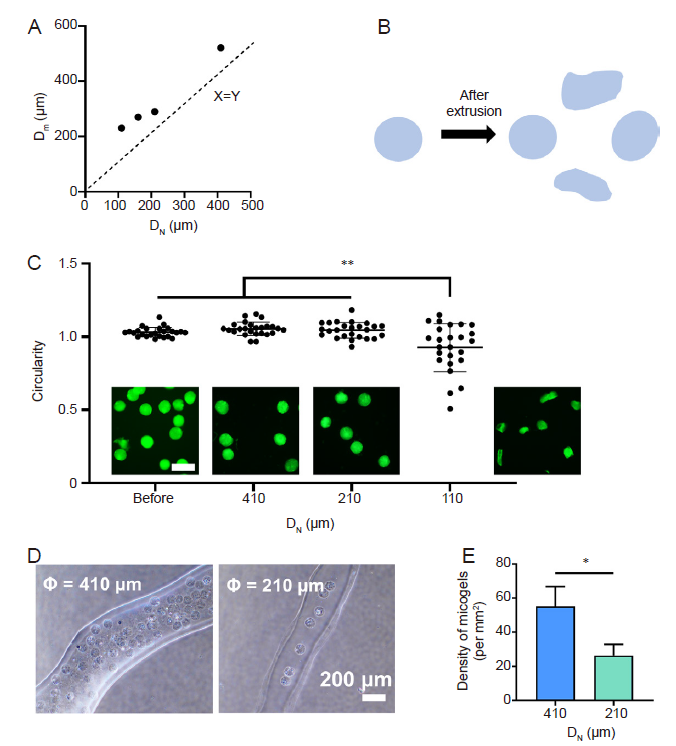

Figure 4. Extrusion of the DM-GelMA hydrogel and preservation of DM morphology. (A) The relationship between different sized needles and their corresponding maximum extrudable DM sizes. DN is the inner diameter of the needles, and Dm is the maximum size of the DMs. The dashed line represents a specific condition when the inner diameter of the needle is equal to the DM size. (B) The schematic diagram illustrates the changes in microgel morphology after extrusion. Created using Microsoft PowerPoint 2020. (C) The circularity of DMs post-extrusion using different sized needles, and representative fluorescence micrographs show the extruded microgels pre-labelled with FITC. Scale bars: 200 μm. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis). (D) The 3D bioprinted filaments extruded from 410- and 210-μm needles, respectively. (E) The density of microgels in the 3D bioprinted filaments using 410- and 210-μm needles. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 (Student's t-test). DM: decellularised extracellular matrix microgel; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; GelMA: gelatin methacryloyl.

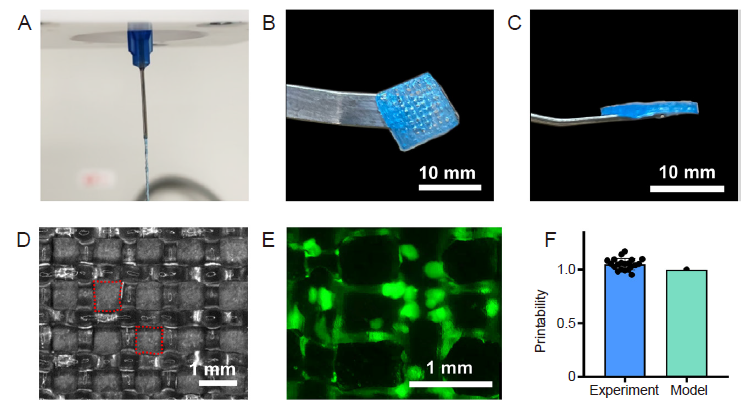

Figure 5. Printability of the DM-GelMA bioink. (A) The DM-GelMA hydrogel was extruded continuously and smoothly, showing a proper-gelation condition for 3D printing. The (B) top-view and (C) side-view of a representative 3D printed grid mesh using DM-GelMA hydrogel. (D) The grid framework 3D printed by DM-GelMA hydrogel, observed by optical microscopy. (E) A representative fluorescence micrograph showed the FITC-labelled DMs (green) embedded in the 3D printed construct. Scale bar: 10 mm (B, C) and 1 mm (D, E). (F) The Pr of the DM-GelMA bioink (“Experiment”) compared with a regular square shape (“Model”, Pr = 1), analysed accordingly to a previously reported semi-quantitative method. 3D: three-dimensional; DM: decellularised extracellular matrix microgel; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; GelMA: gelatin methacryloyl; Pr: printability.

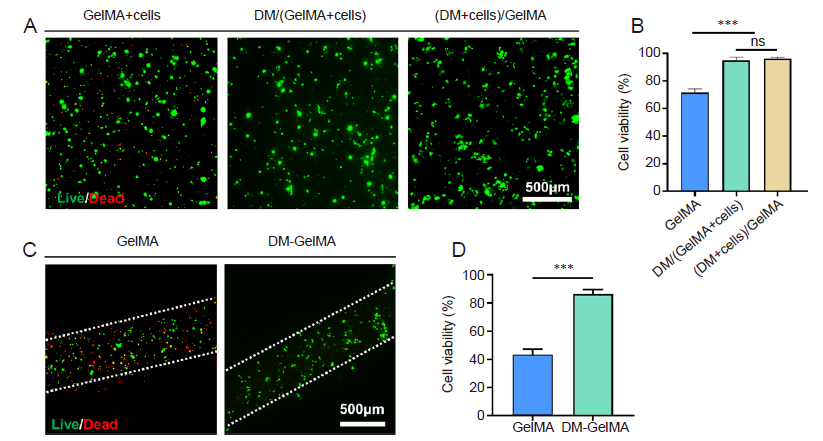

Figure 6. Cell viability in the modular bioinks. (A) Representative fluorescence micrographs after live/dead staining on the PC12 cell-encapsulated bioinks and 3D cultured for 4 days. “GelMA+Cells” represents the bioink that PC12 cells were directly mixed with GelMA solution. “DM/(GelMA+Cells)” represents the bioink consisting of prepared DMs and PC12-cell-encapsulated GelMA solution. “(DM+Cells)/GelMA” denotes the bioink prepared by mixing PC12-cell-encapsulated DMs and GelMA solution. Green: live cells; red: dead cells. (B) Cell viability of the PC12 cells within the abovementioned bioinks based on the fluorescence images shown in A. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis). (C) Representative fluorescence micrographs after live/dead staining on the bioprinted filaments using cell-laden GelMA and DM-GelMA bioinks, respectively. Green: live cells; red: dead cells. Scale bars: 500 μm. (D) Post-printing cell viability based on the fluorescence images shown in C. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test). DM: decellularised extracellular matrix microgel; GelMA: gelatin methacryloyl; ns: no significance.

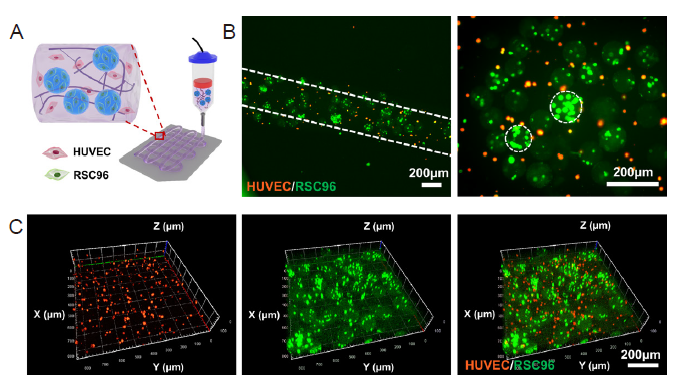

Figure 7. 3D bioprinting of multiscale DM-GelMA bioink for RSC96 cells and HUVECs co-culture. (A) Schematic illustration of extrusion-based bioprinting using HUVECs and RSC96 cell-laden DM-GelMA bioink. Created with 3D Max 2021. (B, C) 2D views (B) and 3D views (C) of the bioprinted 3D constructs using the cell-laden DM-GelMA composite bioink, characterised by confocal laser fluorescence microscopy. RSC96 cells and HUVECs were pre-stained with green and orange Cell Tracker Fluorescent Probes, respectively, prior to cell encapsulation. Scale bars: 200 μm. 2D: two-dimensional; 3D: three-dimensional; DM decellularised extracellular matrix microgel; GelMA: gelatin methacryloyl; HUVEC: human umbilical vein endothelial cell.

Additional Figure 2. The micrographs and the distribution of the diameters of the microgels for Qoil/Qaqu = 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, and 20, respectively. Series of DM preparation showed that the microgel size was highly dependent on the corresponding flow rate ratio, Qoil/Qaqu. With increasing the ratio Qoil/Qaqu, the diameter of the generated microgels decreased gradually. The average diameters of the microgels were 128 ± 7, 114 ± 8, 107 ± 8, 101 ± 5, 82 ± 6, and 77 ± 4 μm for Qoil/Qaqu = 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, and 20, respectively.

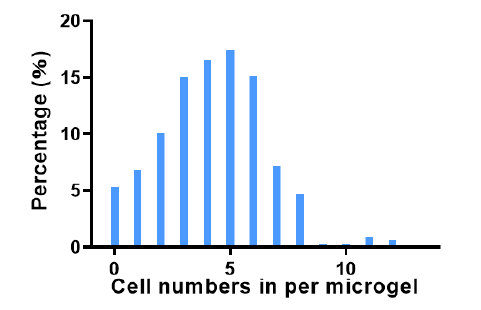

Additional Figure 3. The number of cells encapsulated in each microgel and its corresponding frequency of appearance when observed using confocal laser microscopy (n > 300).

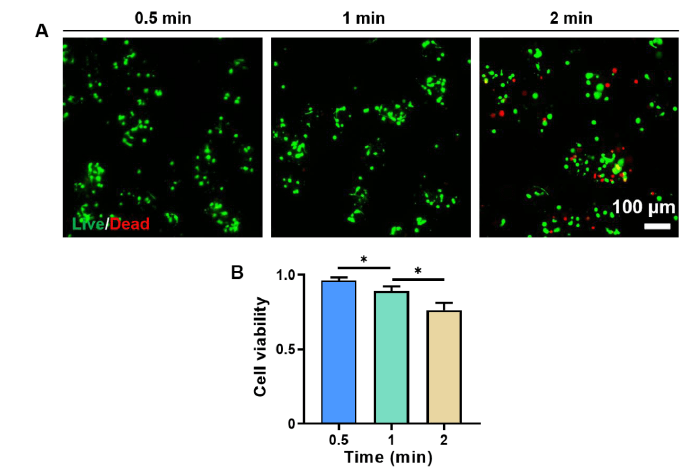

Additional Figure 4. The viability of encapsulated PC12 cells decreased with increasing centrifugation time. (A) Representative fluorescence micrographs of the DM encapsulated cells after 0.5, 1, and 2 minutes of centrifugation, respectively. Characterised by live/dead staining. Green: live cells, red: dead cells. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Cell viability of the PC12 cells encapsulated in the microgels after 0.5, 1, and 2 minutes of centrifugation, respectively. The cell viability was calculated based on the fluorescence images shown in A. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis). DMs: decellularised extracellular matrix microgels.

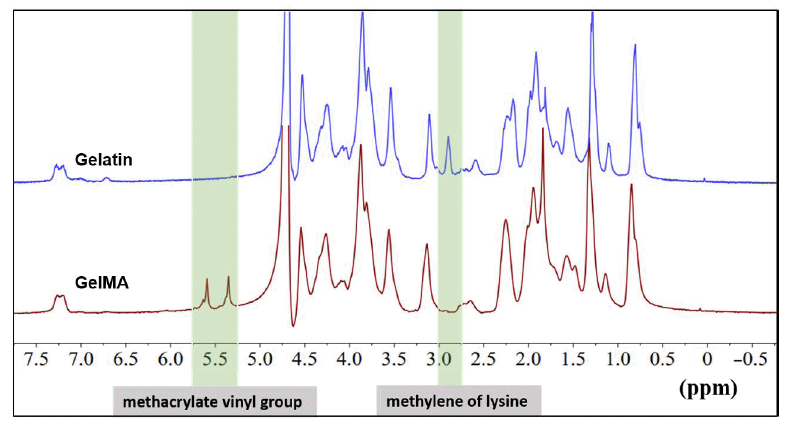

Additional Figure 5. 1H-NMR characterisation of gelatin and GelMA. The characteristic peak of the methacrylate vinyl group at 5.4 and 5.7 ppm, as well as the minor peak shown at 2.9 ppm (the protons of methylene of lysine) verified the successful synthesis of GelMA. 1H-NMR: 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance; GelMA: gelatin methacryloyl.

| 1. |

Daly, A. C.; Prendergast, M. E.; Hughes, A. J.; Burdick, J. A. Bioprinting for the biologist. Cell. 2021, 184, 18-32.

doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.002 URL |

| 2. | Derakhshanfar, S.; Mbeleck, R.; Xu, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, W.; Xing, M. 3D bioprinting for biomedical devices and tissue engineering: A review of recent trends and advances. Bioact Mater. 2018, 3, 144-156. |

| 3. |

Gungor-Ozkerim, P. S.; Inci, I.; Zhang, Y. S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dokmeci, M. R. Bioinks for 3D bioprinting: an overview. Biomater Sci. 2018, 6, 915-946.

doi: 10.1039/C7BM00765E URL |

| 4. | Unagolla, J. M.; Jayasuriya, A. C. Hydrogel-based 3D bioprinting: A comprehensive review on cell-laden hydrogels, bioink formulations, and future perspectives. Appl Mater Today. 2020, 18, 100479. |

| 5. |

Ying, G.; Jiang, N.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Y. S. Three-dimensional bioprinting of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA). Bio-des Manuf. 2018, 1, 215-224.

doi: 10.1007/s42242-018-0028-8 |

| 6. |

Bandyopadhyay, A.; Mandal, B. B.; Bhardwaj, N. 3D bioprinting of photo-crosslinkable silk methacrylate (SilMA)-polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) bioink for cartilage tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2022, 110, 884-898.

doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.v110.4 URL |

| 7. | Lee, J. M.; Suen, S. K. Q.; Ng, W. L.; Ma, W. C.; Yeong, W. Y. Bioprinting of collagen: considerations, potentials, and applications. Macromol Biosci. 2021, 21, e2000280. |

| 8. |

Jia, J.; Richards, D. J.; Pollard, S.; Tan, Y.; Rodriguez, J.; Visconti, R. P.; Trusk, T. C.; Yost, M. J.; Yao, H.; Markwald, R. R.; Mei, Y. Engineering alginate as bioink for bioprinting. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 4323-4331.

doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.06.034 URL |

| 9. |

Gao, Q.; Niu, X.; Shao, L.; Zhou, L.; Lin, Z.; Sun, A.; Fu, J.; Chen, Z.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; He, Y. 3D printing of complex GelMA-based scaffolds with nanoclay. Biofabrication. 2019, 11, 035006.

doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ab0cf6 URL |

| 10. |

Busch, R.; Strohbach, A.; Pennewitz, M.; Lorenz, F.; Bahls, M.; Busch, M. C.; Felix, S. B. Regulation of the endothelial apelin/APJ system by hemodynamic fluid flow. Cell Signal. 2015, 27, 1286-1296.

doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.03.011 URL |

| 11. | Xu, H. Q.; Liu, J. C.; Zhang, Z. Y.; Xu, C. X. A review on cell damage, viability, and functionality during 3D bioprinting. Mil Med Res. 2022, 9, 70. |

| 12. | Adhikari, J.; Roy, A.; Das, A.; Ghosh, M.; Thomas, S.; Sinha, A.; Kim, J.; Saha, P. Effects of Processing parameters of 3D bioprinting on the cellular activity of bioinks. Macromol Biosci. 2021, 21, e2000179. |

| 13. |

Luan, C.; Liu, P.; Chen, R.; Chen, B. Hydrogel based 3D carriers in the application of stem cell therapy by direct injection. Nanotechnol Rev. 2017, 6, 435-448.

doi: 10.1515/ntrev-2017-0115 URL |

| 14. | Highley, C. B.; Song, K. H.; Daly, A. C.; Burdick, J. A. Jammed microgel inks for 3D printing applications. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2019, 6, 1801076. |

| 15. |

Daly, A. C.; Riley, L.; Segura, T.; Burdick, J. A. Hydrogel microparticles for biomedical applications. Nat Rev Mater. 2020, 5, 20-43.

doi: 10.1038/s41578-019-0148-6 |

| 16. |

Fang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ji, M.; Li, B.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, T.; Xiong, Z. 3D printing of cell-laden microgel-based biphasic bioink with heterogeneous microenvironment for biomedical applications. Adv Funct Mater. 2022, 32, 2109810.

doi: 10.1002/adfm.v32.13 URL |

| 17. |

Chen, J.; Huang, D.; Wang, L.; Hou, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhong, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huang, W. 3D bioprinted multiscale composite scaffolds based on gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA)/chitosan microspheres as a modular bioink for enhancing 3D neurite outgrowth and elongation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 574, 162-173.

doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2020.04.040 URL |

| 18. | Xin, S.; Deo, K. A.; Dai, J.; Pandian, N. K. R.; Chimene, D.; Moebius, R. M.; Jain, A.; Han, A.; Gaharwar, A. K.; Alge, D. L. Generalizing hydrogel microparticles into a new class of bioinks for extrusion bioprinting. Sci Adv. 2021, 7, eabk3087. |

| 19. |

Feng, Q.; Li, D.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Lin, Z.; Cao, X.; Dong, H. Assembling microgels via dynamic cross-linking reaction improves printability, microporosity, tissue-adhesion, and self-healing of microgel bioink for extrusion bioprinting. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022, 14, 15653-15666.

doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c01295 URL |

| 20. |

Zhao, X.; Liu, S.; Yildirimer, L.; Zhao, H.; Ding, R.; Wang, H.; Cui, W.; Weitz, D. Injectable stem cell-laden photocrosslinkable microspheres fabricated using microfluidics for rapid generation of osteogenic tissue constructs. Adv Funct Mater. 2016, 26, 2809-2819.

doi: 10.1002/adfm.v26.17 URL |

| 21. |

An, C.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Liao, H.; Ren, C.; Wang, H. Continuous microfluidic encapsulation of single mesenchymal stem cells using alginate microgels as injectable fillers for bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2020, 111, 181-196.

doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.05.024 URL |

| 22. |

Riederer, M. S.; Requist, B. D.; Payne, K. A.; Way, J. D.; Krebs, M. D. Injectable and microporous scaffold of densely-packed, growth factor-encapsulating chitosan microgels. Carbohydr Polym. 2016, 152, 792-801.

doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.07.052 URL |

| 23. |

Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, S.; Gao, F.; Guo, W.; Sun, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Rao, Z.; Qiu, S.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, X.; Guo, X.; Shao, Z.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Quan, D. Understanding the role of tissue-specific decellularized spinal cord matrix hydrogel for neural stem/progenitor cell microenvironment reconstruction and spinal cord injury. Biomaterials. 2021, 268, 120596.

doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120596 URL |

| 24. |

Kim, B. S.; Das, S.; Jang, J.; Cho, D. W. Decellularized extracellular matrix-based bioinks for engineering tissue- and organ-specific microenvironments. Chem Rev. 2020, 120, 10608-10661.

doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00808 URL |

| 25. |

Lin, Z.; Rao, Z.; Chen, J.; Chu, H.; Zhou, J.; Yang, L.; Quan, D.; Bai, Y. Bioactive decellularized extracellular matrix hydrogel microspheres fabricated using a temperature-controlling microfluidic system. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022, 8, 1644-1655.

doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c01474 URL |

| 26. | Abaci, A.; Guvendiren, M. Designing decellularized extracellular matrix-based bioinks for 3D bioprinting. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020, 9, e2000734. |

| 27. |

Wang, T.; Han, Y.; Wu, Z.; Qiu, S.; Rao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, Q.; Quan, D.; Bai, Y.; Liu, X. Tissue-specific hydrogels for three-dimensional printing and potential application in peripheral nerve regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2022, 28, 161-174.

doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2021.0093 URL |

| 28. |

Kim, M. K.; Jeong, W.; Lee, S. M.; Kim, J. B.; Jin, S.; Kang, H. W. Decellularized extracellular matrix-based bio-ink with enhanced 3D printability and mechanical properties. Biofabrication. 2020, 12, 025003.

doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ab5d80 URL |

| 29. |

Li, X.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Kawazoe, N.; Chen, G. 3D culture of chondrocytes in gelatin hydrogels with different stiffness. Polymers (Basel). 2016, 8, 269.

doi: 10.3390/polym8080269 URL |

| 30. |

Fairbanks, B. D.; Schwartz, M. P.; Bowman, C. N.; Anseth, K. S. Photoinitiated polymerization of PEG-diacrylate with lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate: polymerization rate and cytocompatibility. Biomaterials. 2009, 30, 6702-6707.

doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.055 URL |

| 31. | Schneider, C. A.; Rasband, W. S.; Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012, 9, 671-675. |

| 32. |

Ouyang, L.; Yao, R.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, W. Effect of bioink properties on printability and cell viability for 3D bioplotting of embryonic stem cells. Biofabrication. 2016, 8, 035020.

doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/8/3/035020 URL |

| 33. | Gal, I.; Edri, R.; Noor, N.; Rotenberg, M.; Namestnikov, M.; Cabilly, I.; Shapira, A.; Dvir, T. Injectable cardiac cell microdroplets for tissue regeneration. Small. 2020, 16, e1904806. |

| 34. |

Akartuna, I.; Aubrecht, D. M.; Kodger, T. E.; Weitz, D. A. Chemically induced coalescence in droplet-based microfluidics. Lab Chip. 2015, 15, 1140-1144.

doi: 10.1039/C4LC01285B URL |

| 35. |

Zheng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Khan, M.; Mao, S.; Manibalan, K.; Li, N.; Lin, J. M.; Lin, L. Multifunctional regulation of 3D cell-laden microsphere culture on an integrated microfluidic device. Anal Chem. 2019, 91, 12283-12289.

doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02434 URL |

| 36. |

Xu, J.; Fang, H.; Zheng, S.; Li, L.; Jiao, Z.; Wang, H.; Nie, Y.; Liu, T.; Song, K. A biological functional hybrid scaffold based on decellularized extracellular matrix/gelatin/chitosan with high biocompatibility and antibacterial activity for skin tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021, 187, 840-849.

doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.162 URL |

| 37. |

Ning, L.; Yang, B.; Mohabatpour, F.; Betancourt, N.; Sarker, M. D.; Papagerakis, P.; Chen, X. Process-induced cell damage: pneumatic versus screw-driven bioprinting. Biofabrication. 2020, 12, 025011.

doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ab5f53 URL |

| 38. |

Rao, Z.; Lin, Z.; Song, P.; Quan, D.; Bai, Y. biomaterial-based schwann cell transplantation and Schwann cell-derived biomaterials for nerve regeneration. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 926222.

doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.926222 URL |

| 39. |

Ogunshola, O. O.; Antic, A.; Donoghue, M. J.; Fan, S. Y.; Kim, H.; Stewart, W. B.; Madri, J. A.; Ment, L. R. Paracrine and autocrine functions of neuronal vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the central nervous system. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277, 11410-11415.

doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111085200 URL |

| 40. |

Zou, J. L.; Liu, S.; Sun, J. H.; Yang, W. H.; Xu, Y. W.; Rao, Z. L.; Jiang, B.; Zhu, Q. T.; Liu, X. L.; Wu, J. L.; Chang, C.; Mao, H. Q.; Ling, E. A.; Quan, D. P.; Zeng, Y. S. Peripheral nerve-derived matrix hydrogel promotes remyelination and inhibits synapse formation. Adv Funct Mater. 2018, 28, 1705739.

doi: 10.1002/adfm.v28.13 URL |

| 41. |

Chen, S.; Du, Z.; Zou, J.; Qiu, S.; Rao, Z.; Liu, S.; Sun, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, X.; Mao, H. Q.; Bai, Y.; Quan, D. Promoting neurite growth and schwann cell migration by the harnessing decellularized nerve matrix onto nanofibrous guidance. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019, 11, 17167-17176.

doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b01066 URL |

| No related articles found! |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||