Biomaterials Translational ›› 2021, Vol. 2 ›› Issue (2): 91-142.doi: 10.12336/biomatertransl.2021.02.003

• REVIEW • Previous Articles Next Articles

Yizhong Peng1, Xiangcheng Qing1, Hongyang Shu2,3, Shuo Tian1, Wenbo Yang1, Songfeng Chen4, Hui Lin1, Xiao Lv1, Lei Zhao1, Xi Chen1, Feifei Pu1, Donghua Huang4, Xu Cao5,*( ), Zengwu Shao1,*(

), Zengwu Shao1,*( )

)

Received:2021-04-08

Revised:2021-06-04

Accepted:2021-06-09

Online:2021-06-28

Published:2021-06-28

Contact:

Xu Cao,Zengwu Shao

E-mail:xcao11@jhmi.edu, szwpro@163.com

Peng, Y.; Qing, X.; Shu, H.; Tian, S.; Yang, W.; Chen, S.; Lin, H.; Lv, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, X.; Pu, F.; Huang, D.; Cao, X.; Shao, Z. Proper animal experimental designs for preclinical research of biomaterials for intervertebral disc regeneration. Biomater Transl. 2021, 2(2), 91-142.

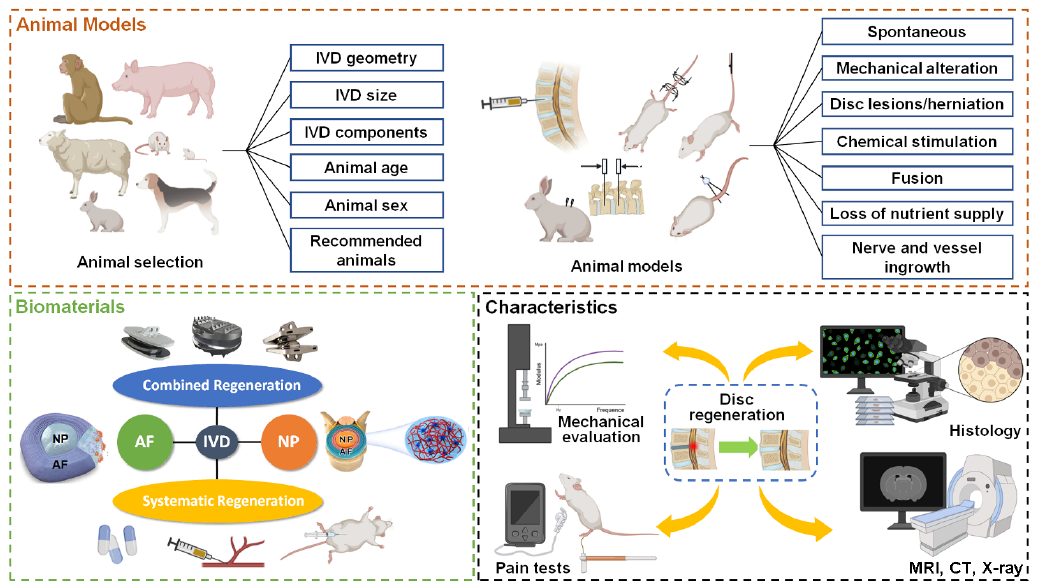

Figure 2. The structural diagram of this review. AF: annulus fibrosus; CT: computed tomography; IVD: intervertebral disc; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NP: nucleus pulposus.

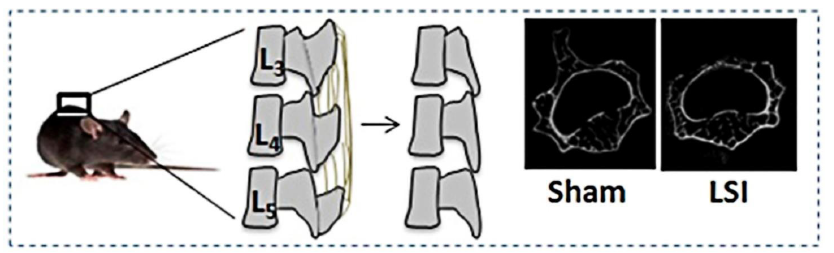

Figure 3. Lumbar spine instability mouse model (LSI). Mouse L3-5 spinous processes were resected along with the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments to induce instability of lumbar spine. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd.: Bian et al.83 Copyright 2016.

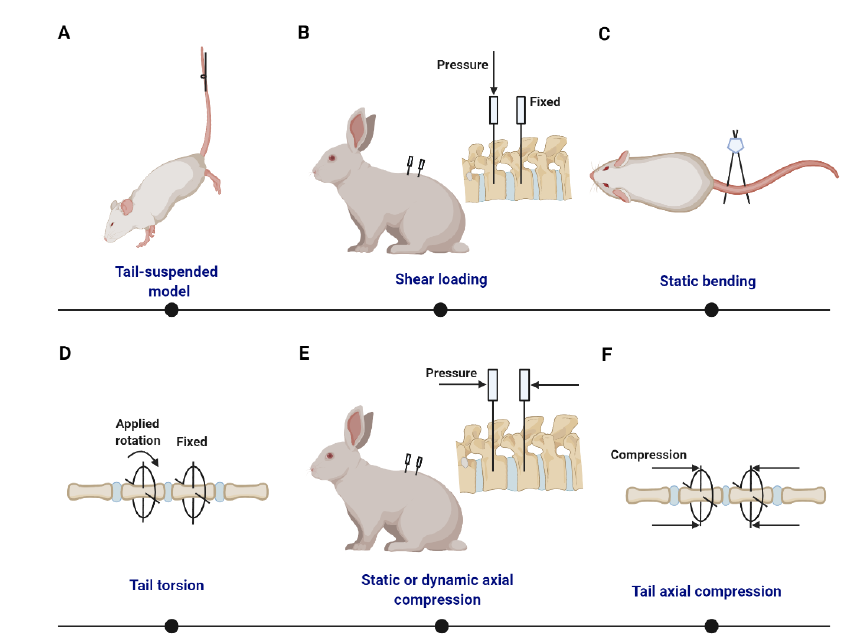

Figure 4. Summary of static/dynamic compression models with external apparatus. (A) Tail-suspended rat with its hind limbs off the floor.272 (B) Shear loading is generated from forces of different magnitudes on the adjecant vertebrae.281, 282 (C) Static disc bending model based on pins and an alignment jig.283 (D) Ilizarov-type apparatus is used to produce tail torsion. (E) Surgically implanted transfixing pins and percutaneous posts allow the application of static or dynamic axial compression and distraction loading at a single level of the rabbit lumbar spine.284 (F) Ilizarov-type apparatus is used to produce tail axial compression.

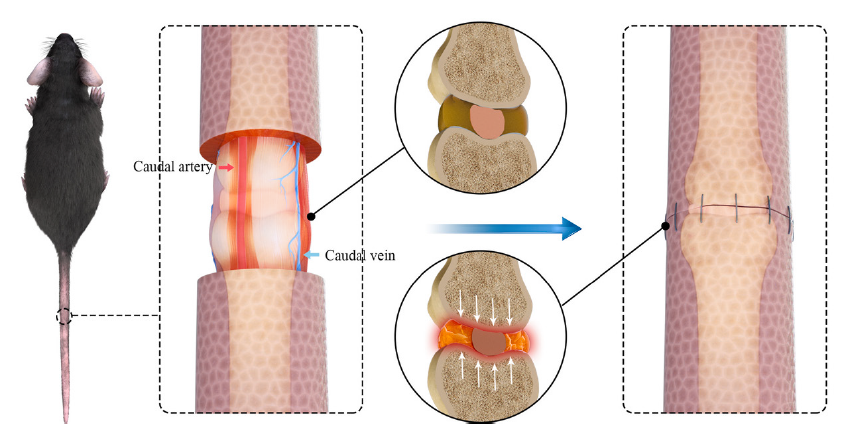

Figure 5. Compressive suture-induced rat IDD model. Circumcising the skin around index discs with a width of 2 mm and anastomosing the skin impose axial compression on the tail. Reprinted from Liu et al.292 Copyright ? 2021 with permission from Elsevier. IDD: intervertebral disc degeneration.

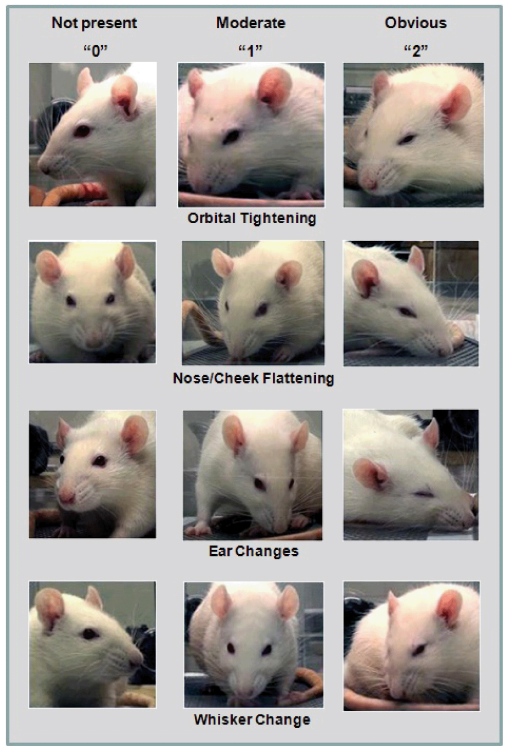

Figure 6. Scales for spontaneous pain evaluation based on rodent facial expressions. Copyright ?2011 Sotocinal et al.675 Reprinted from BioMed Central Ltd.

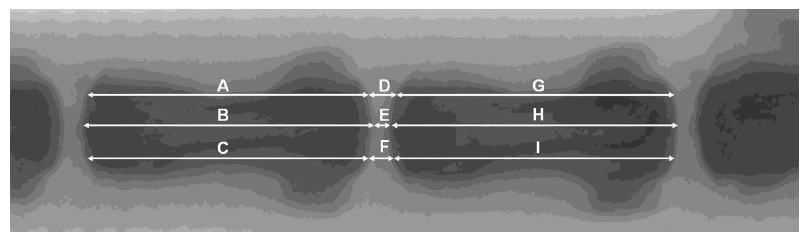

Figure 7. Measurements and calculations of vertebral body height and IVD height based on radiographs. The IVD height should be quantified using a relative value, %DHI, which measures changes in the DHI of punctured discs. DHI = 2 × (D + E + F) / (A + B + C + G + H + I); %DHI = post-punctured DHI / pre-punctured DHI × 100. DHI: disc height index; IVD: intervertebral disc.313

| Model type | Species | Manipulation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disc disruption | |||

| Spontaneous | Mouse | Aging | |

| Ercc1 mutation | |||

| Cmd aggrecan knockout | |||

| Inherited kyphoscoliosis | |||

| Collagen II mutation | |||

| Collagen IX mutation | |||

| Myostatin knockout | |||

| Defect at ank locus, ankylosing spondylitis | |||

| twy mouse—IVD calcification and ankylosis | |||

| SPARC null | |||

| HLA B27 transgenic, spondylolisthesis | |||

| Rat | Aging | ||

| Sand rat | Chondrodystrophy, aging, breed | ||

| Dog | Spondylosis; aging | ||

| Chinese hamster | Aging | ||

| Baboon | Aging | ||

| Mechanical alteration | Mouse | Lumbar spine instability mouse model with/without ovariectomy | |

| Mouse, rat | Static compression | ||

| Rabbit | Shear stress | ||

| Rabbit | Compression injury, lumbar spine and caudal disc compression | ||

| Rat | Tail suspension | ||

| Shear stress | |||

| Amputation of upper limbs and tail | |||

| Mouse | Amputation of upper limbs | ||

| Rabbit | Resection of the cervical supraspinous and interspinous ligaments and detachment of the posterior paravertebral muscles from the cervical vertebrae; the removal of facet joints | ||

| Dog | Static compression | ||

| Pig | Resection of facet joint, interspinous and anterior ligament injury | ||

| Rabbit | Facetectomy/capsulotomy torsional lumbar injury | ||

| Disc herniation | Cavine | A partial laminectomy of the caudal part of the | |

| Rat | NP obtained from tail amputation and placed on nerve root | ||

| Rabbit | Bilateral facet joint resection at L7﹣S1 and rotational manipulation | ||

| External annular wound (2 mm) | |||

| Rat | Flexion, lateral bending and rotational forces | ||

| Disc lesions | Rabbit | Multiple 5 mm stab incisions using 16, 18 or 21G needles | |

| NP removal | |||

| 3﹣5 mm outer anterolateral annular incision (rim-lesion) | |||

| Ovine | Circumferential annular tear (delamellation) | ||

| A lateral retroperitoneal drill bit injury | |||

| Anular lesion by surgical incision through the left anterolateral AF | |||

| Pig | Combined lesions in AF (1.2 cm), NP (1.5 cm), facet joint and capsule | ||

| Rat | 5 mm stab by 18﹣30G needles | ||

| Dog | 4 mm posterior annulotomy | ||

| Local chemical stimulation | Rat | Chondroitinase ABC | |

| Rabbit | |||

| Sheep | |||

| Macaque | Chymopapain | ||

| Rabbit | Chymopapain | ||

| Rhesus monkeys | Pingyangmycin | ||

| Bleomycin | |||

| Dog | Fibronectin fragments | ||

| Rabbit | Fibronectin fragments | ||

| Chymopapain, krill proteases | |||

| Rat | Complete Freund's adjuvant | ||

| Rat | IL-1β | ||

| Rat | AGE | ||

| Systematic reagents stimulation | Mouse | Immunized with aggrecan and/or versican, develops spondylitis | |

| Dietary AGE | |||

| Diabetic | |||

| Fusion | Rabbit | Lumbar arthrodesis | |

| Sheep | Lumbar arthrodesis | ||

| Rat | Lumbar arthrodesis | ||

| Rabbit | Controlled dynamic distraction | ||

| Pinealectomy models of scoliosis | Chicken | Pinealectomy | |

| Rat | Pinealectomy + bipedal | ||

| Appendix | |||

| Loss of nutrient supply | Mouse, rat | Endplate perforation | |

| Pig | Disc allograft transplantation | ||

| Endplate perforation and cryoinjury | |||

| Goat | Ethanol injection to bone marrow vertebrae body | ||

| Cement injection to the adjecant vertebrae body | |||

| Rat | Nd: YAG laser on the CEP of the degenerated IVD | ||

| Nerves and vessels ingrowth | Pig | Annulus fibrosus puncture and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)/fibrin gel sealing | |

| Mouse | Disc puncture and nucleus pulposus removal | ||

| Sheep | Annulus fibrosus puncture | ||

| Nerve associated degeneration | Rabbit | Surgical narrowing of intervertebral neural foramen, vibrational stimulation of dorsal root ganglia | |

| Others | |||

| Hyperactivity | Dog | Long distance running training |

Additional Table 1 Animal models used to study disc degeneration

| Model type | Species | Manipulation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disc disruption | |||

| Spontaneous | Mouse | Aging | |

| Ercc1 mutation | |||

| Cmd aggrecan knockout | |||

| Inherited kyphoscoliosis | |||

| Collagen II mutation | |||

| Collagen IX mutation | |||

| Myostatin knockout | |||

| Defect at ank locus, ankylosing spondylitis | |||

| twy mouse—IVD calcification and ankylosis | |||

| SPARC null | |||

| HLA B27 transgenic, spondylolisthesis | |||

| Rat | Aging | ||

| Sand rat | Chondrodystrophy, aging, breed | ||

| Dog | Spondylosis; aging | ||

| Chinese hamster | Aging | ||

| Baboon | Aging | ||

| Mechanical alteration | Mouse | Lumbar spine instability mouse model with/without ovariectomy | |

| Mouse, rat | Static compression | ||

| Rabbit | Shear stress | ||

| Rabbit | Compression injury, lumbar spine and caudal disc compression | ||

| Rat | Tail suspension | ||

| Shear stress | |||

| Amputation of upper limbs and tail | |||

| Mouse | Amputation of upper limbs | ||

| Rabbit | Resection of the cervical supraspinous and interspinous ligaments and detachment of the posterior paravertebral muscles from the cervical vertebrae; the removal of facet joints | ||

| Dog | Static compression | ||

| Pig | Resection of facet joint, interspinous and anterior ligament injury | ||

| Rabbit | Facetectomy/capsulotomy torsional lumbar injury | ||

| Disc herniation | Cavine | A partial laminectomy of the caudal part of the | |

| Rat | NP obtained from tail amputation and placed on nerve root | ||

| Rabbit | Bilateral facet joint resection at L7﹣S1 and rotational manipulation | ||

| External annular wound (2 mm) | |||

| Rat | Flexion, lateral bending and rotational forces | ||

| Disc lesions | Rabbit | Multiple 5 mm stab incisions using 16, 18 or 21G needles | |

| NP removal | |||

| 3﹣5 mm outer anterolateral annular incision (rim-lesion) | |||

| Ovine | Circumferential annular tear (delamellation) | ||

| A lateral retroperitoneal drill bit injury | |||

| Anular lesion by surgical incision through the left anterolateral AF | |||

| Pig | Combined lesions in AF (1.2 cm), NP (1.5 cm), facet joint and capsule | ||

| Rat | 5 mm stab by 18﹣30G needles | ||

| Dog | 4 mm posterior annulotomy | ||

| Local chemical stimulation | Rat | Chondroitinase ABC | |

| Rabbit | |||

| Sheep | |||

| Macaque | Chymopapain | ||

| Rabbit | Chymopapain | ||

| Rhesus monkeys | Pingyangmycin | ||

| Bleomycin | |||

| Dog | Fibronectin fragments | ||

| Rabbit | Fibronectin fragments | ||

| Chymopapain, krill proteases | |||

| Rat | Complete Freund's adjuvant | ||

| Rat | IL-1β | ||

| Rat | AGE | ||

| Systematic reagents stimulation | Mouse | Immunized with aggrecan and/or versican, develops spondylitis | |

| Dietary AGE | |||

| Diabetic | |||

| Fusion | Rabbit | Lumbar arthrodesis | |

| Sheep | Lumbar arthrodesis | ||

| Rat | Lumbar arthrodesis | ||

| Rabbit | Controlled dynamic distraction | ||

| Pinealectomy models of scoliosis | Chicken | Pinealectomy | |

| Rat | Pinealectomy + bipedal | ||

| Appendix | |||

| Loss of nutrient supply | Mouse, rat | Endplate perforation | |

| Pig | Disc allograft transplantation | ||

| Endplate perforation and cryoinjury | |||

| Goat | Ethanol injection to bone marrow vertebrae body | ||

| Cement injection to the adjecant vertebrae body | |||

| Rat | Nd: YAG laser on the CEP of the degenerated IVD | ||

| Nerves and vessels ingrowth | Pig | Annulus fibrosus puncture and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)/fibrin gel sealing | |

| Mouse | Disc puncture and nucleus pulposus removal | ||

| Sheep | Annulus fibrosus puncture | ||

| Nerve associated degeneration | Rabbit | Surgical narrowing of intervertebral neural foramen, vibrational stimulation of dorsal root ganglia | |

| Others | |||

| Hyperactivity | Dog | Long distance running training |

| Gauge number | Needle nominal O.D. (mm) | Needle nominal I.D. (mm) | Needle wall thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10G | 3.404 | 2.693 | 0.356 |

| 11G | 3.048 | 2.388 | 0.33 |

| 12G | 2.769 | 2.159 | 0.305 |

| 13G | 2.413 | 1.804 | 0.305 |

| 14G | 2.109 | 1.6 | 0.254 |

| 15G | 1.829 | 1.372 | 0.229 |

| 16G | 1.651 | 1.194 | 0.229 |

| 17G | 1.473 | 1.067 | 0.203 |

| 18G | 1.27 | 0.838 | 0.216 |

| 19G | 1.067 | 0.686 | 0.191 |

| 20G | 0.908 | 0.603 | 0.152 |

| 21G | 0.819 | 0.514 | 0.152 |

| 22G | 0.718 | 0.413 | 0.152 |

| 23G | 0.642 | 0.337 | 0.152 |

| 24G | 0.566 | 0.311 | 0.127 |

| 25G | 0.515 | 0.26 | 0.127 |

| 26G | 0.464 | 0.26 | 0.102 |

| 27G | 0.413 | 0.21 | 0.102 |

| 28G | 0.362 | 0.184 | 0.089 |

| 29G | 0.337 | 0.184 | 0.076 |

| 30G | 0.312 | 0.159 | 0.076 |

| 31G | 0.261 | 0.133 | 0.064 |

| 32G | 0.235 | 0.108 | 0.064 |

| 33G | 0.21 | 0.108 | 0.051 |

| 34G | 0.159 | 0.051 | 0.051 |

Additional Table 2 Needle gauge and corresponding size

| Gauge number | Needle nominal O.D. (mm) | Needle nominal I.D. (mm) | Needle wall thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10G | 3.404 | 2.693 | 0.356 |

| 11G | 3.048 | 2.388 | 0.33 |

| 12G | 2.769 | 2.159 | 0.305 |

| 13G | 2.413 | 1.804 | 0.305 |

| 14G | 2.109 | 1.6 | 0.254 |

| 15G | 1.829 | 1.372 | 0.229 |

| 16G | 1.651 | 1.194 | 0.229 |

| 17G | 1.473 | 1.067 | 0.203 |

| 18G | 1.27 | 0.838 | 0.216 |

| 19G | 1.067 | 0.686 | 0.191 |

| 20G | 0.908 | 0.603 | 0.152 |

| 21G | 0.819 | 0.514 | 0.152 |

| 22G | 0.718 | 0.413 | 0.152 |

| 23G | 0.642 | 0.337 | 0.152 |

| 24G | 0.566 | 0.311 | 0.127 |

| 25G | 0.515 | 0.26 | 0.127 |

| 26G | 0.464 | 0.26 | 0.102 |

| 27G | 0.413 | 0.21 | 0.102 |

| 28G | 0.362 | 0.184 | 0.089 |

| 29G | 0.337 | 0.184 | 0.076 |

| 30G | 0.312 | 0.159 | 0.076 |

| 31G | 0.261 | 0.133 | 0.064 |

| 32G | 0.235 | 0.108 | 0.064 |

| 33G | 0.21 | 0.108 | 0.051 |

| 34G | 0.159 | 0.051 | 0.051 |

| Animal | Needle size | Needle diameter/disc height (%) | Approach | Depth | Puncture position | Segements | Additional | Degenerated time point/longest recorded time | Mechanical | Biochemical | Height (longest recorded time) | Histologic and gross | Radiograph and MRI | Neuropathic pain | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | 18G | 128% | Open/percutaneous puncture | Needle bevel completely inserted | Tail | C3/4 | - | 1/4 months | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in open puncture) | Yes, progressed (more severe in open puncture) | |||||

| 20G | 95% | Percutaneous puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus); 10 mm (full penetration) | Tail | C6/7﹣C9/10 | - | 2﹣4/4﹣8 weeks | - | Decreased GAG (by ~11% for 5 mm, by ~16% for 10 mm) | Decreased (by ~10% for 5 mm; by ~20% for 10 mm) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in full penetration) | Yes, progressed (more severe in full penetration) | Yes | |||||

| 20G | 95% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Tail | C6/7﹣C8/9 | - | 1﹣4/4﹣24 weeks | - | Decreased water, GAG and type I collagen expression | Decreased (by 25-75%) | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Open puncture | 3 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Posterial approach | L4/5 | - | 4/8 weeks | - | Altered collagens expression | - | - | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Open puncture | 3 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Posterior/anterior approach | L4/5 | - | 2/6 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | Yes (more significant for posterior puncture) | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Open puncture | 3 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C4/5, C8/9 | - | 2 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | Yes | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C5/6, C7/8 | - | 4 weeks | - | Altered collagens expression | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Tail | C4/5﹣C8/9 | - | 1﹣2/14﹣42 days | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 23G | 64% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Lateral approach | L5/6 | Repetitive puncture for five times | 1/2 weeks | - | - | - | - | - | Yes, increased neurons staining | |||||

| 27G | 51% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Dorsal approach | L4/5, L5/6 | - | 2/8 weeks | - | Altered collagens, SOX9, aggrecan expression | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | - | ||||||

| 31G | 26% | Percutaneous puncture | 1.5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C6/7 | - | 4 weeks | - | Altered collagens, aggrecan, MMP13, Adamts4 expression | - | - | - | ||||||

| 18G/22G | 128%/74% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Tail | C6/7, C8/9 | - | 2/4 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | - | - | |||||

| 18G/22G/26G | 128%/74%/20% | Percutaneous puncture | 2 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C6/7, C8/9 | - | 1/4 weeks | Altered creep behavior (for 18G) | - | Yes, degenerated (more severe for 18G) | Yes, progressed | - | ||||||

| 18/20/22G | 128%/95%/74% | Percutaneous puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C6/7, C8/9 | - | 2/8 weeks | - | Increased proteoglycan (for 18G, 20G) | Decreased (for 18G) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in 18G) | Yes, progressed (more severe in 18G) | ||||||

| 18/21/23/ 25/27/29G | 128%/85%/64%/ 53%/51%/36% | Percutaneous puncture | 5 cmm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | NA | - | 2/8﹣12 weeks | - | Altered collagens, SOX9, aggrecan expression | Decreased (by ~10% for 29/27/25G, by ~30% for 23/21G, by ~35% for 18G) | Yes, degenerated (more severe in 18G) | Yes, progressed (more severe in 18G) | ||||||

| 16G/18G/26G | 170%/128%/50% | Percutaneous puncture | Full penetration | Tail | C8/9 | - | 2/4 weeks | - | Altered Collagens expression | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in 16G, 18G) | Yes, progressed (more severe in 16G, 18G) | |||||||

| Mice | 26G | 100% | Percutaneous puncture | 2/3 of the disc thickness | Tail | C3/4﹣C6/7 | - | 4﹣8/4﹣32 weeks | - | Altered Collagens, MMPs, Adam8, Cxcl-1 expression | - | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | - | - | ||||

| 27G | 90% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Anterior approach | L3/4, L4/5 | - | 1/7 days | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | - | - | |||||

| 30G | 63% | Percutaneous puncture | Needle bevel completely inserted | Tail | NA | - | 14 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~25%) | Yes, degenerated | - | - | |||||

| 31G | 55% | Open puncture | 1 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C9/10 | - | 1/12 weeks | - | Altered collagens, GAG, aggrecan expression | Decreased (by ~30%) | Yes, degenerated | - | - | |||||

| 26G/29G | 100%/65% | Percutaneous puncture | 1.75 mm or 90% of the dorsoventral width | Dorsal approach | C6/7-C8/9 | - | 8 weeks | Decreased compressive stiffness, torsional stiffness, torque range, nc compressive ROM, increased creep displacement (for 26G) | Decreased GAG (by ~30% for 26G) | Decreased (by ~30% for 26G) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | - | - | |||||

| 27G/29G/31G | 90%/70%/55% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus/full penetration | Tail | C7/8, C9/10 | - | 4 weeks | - | - | NS | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in full penetration) | Yes, progressed (more severe in full penetration) | ||||||

| 27/30/33G | 90%/63%/40% | Open puncture | NA | Ventral approach | L4/5﹣L6/S1 | - | 1/8 weeks | - | Decreased GAG expression (for 27G and 30G) | Yes, degenerated (more severe for 27G and 30G) | - | |||||||

| 33G/35G | 50%/42% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Ventral/central/dorsal approach | L4/5 | - | 1/12 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated (more severe in central/dorsal approach) | Yes, progressed (more severe in central/dorsal approach) | ||||||

| Rabbit | 16G | 66% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Lateral approach | L2/3﹣L4/5 | NP removal with negative pressure | 6/12 weeks | - | Decreased collagen X expression | Decreased (by ~25%) | Yes, degenerated | - | - | ||||

| 16G | 66% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Posterolateral approach | L3/4, L5/6 | - | 4/12 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~45%) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 16G | 66% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterolateral approach | L2/3﹣L6/7 | NP removal with negative pressure | 2﹣8/12﹣24 weeks | Decreased ROM, increased creep displacement | Altered GAG, collagens, aggrecan, MMP3, SOX9 expression | Decreased (by ~25%) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 18G | 50% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterior/lateral approach | L2/3﹣L6/7 | NP removal with negative pressure | 1﹣4/4﹣14 weeks | - | Decreased GAG, proteoglycan (by ~30%) | Decreased (by ~30%) | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 18G | 50% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Lateral approach | L5/6 | NP removal with negative pressure | 1﹣4/4﹣12 weeks | - | Decreased GAG, collagens expression | Decreased (by ~50%) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 18G | 50% | Open puncture | 1 mm (superfical annulus defect); 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterior approach | L2/3﹣L4/5 | - | 2/12﹣24 weeks | - | - | Decreased (NS for 1 mm puncture, by ~25% for 5 mm puncture) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (for 5 mm puncture) | Yes, progressed (for 5 mm puncture) | ||||||

| 19G | 44% | Percutaneous puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Posterolateral approach | L2/3﹣L4/5 | NP removal with negative pressure | 9/20 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~40%) | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 21G | 27% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterior approach | L3/4﹣L5/6 | NP removal with negative pressure | 4/12﹣28 weeks | - | Decreased proteoglycan expression | - | Yes, degenerated | - | - | |||||

| 16/18/21G | 66%/50%/27% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterior approach | L2/3﹣L5/6 | - | 4/8 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~30% for 16G, by ~10% for 18G/21G) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (for 16G/18G) | Yes, progressed (for 16G/18G) | ||||||

| Pig | 3.2 mm diameter trephine | 62% | Open puncture | NA | Anterolateral approach | NA | - | 8/39 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~15%) | Yes, degenerated | - | - | ||||

| 16G | 30% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Anterolateral approach | L2/5 | NP removal with negative pressure | 3/12﹣24 weeks | - | Altered Collagens, MMPs, aggrecan, TIMPs expression | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | ||||||

| 20G | 17% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | NA | L2/3, L4/5 | NP removal with negative pressure | 12/24 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| Rhesus monkeys | 15G/20G | 41%/20% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Anterolateral approach | L1/2﹣L5/6 | - | 4/12 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated (more severe in 15G) | Yes, progressed (more severe in 15G) | |||||

| Ovine | 3.2-4.5 mm drill | 94﹣100% | Open puncture | 9﹣15 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Lateral approach | L1/2﹣L5/6 | - | 16 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | ||||

| CD-Canine | NA | 30﹣50% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Dorsal approach | L1/2, L3/4, L5/6 | - | 14 weeks | - | Altered aggrecan, collagens expression | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | ||||

Additional Table 3 Parameters for needle puncture-induced intervertebral disc degeneration models

| Animal | Needle size | Needle diameter/disc height (%) | Approach | Depth | Puncture position | Segements | Additional | Degenerated time point/longest recorded time | Mechanical | Biochemical | Height (longest recorded time) | Histologic and gross | Radiograph and MRI | Neuropathic pain | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | 18G | 128% | Open/percutaneous puncture | Needle bevel completely inserted | Tail | C3/4 | - | 1/4 months | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in open puncture) | Yes, progressed (more severe in open puncture) | |||||

| 20G | 95% | Percutaneous puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus); 10 mm (full penetration) | Tail | C6/7﹣C9/10 | - | 2﹣4/4﹣8 weeks | - | Decreased GAG (by ~11% for 5 mm, by ~16% for 10 mm) | Decreased (by ~10% for 5 mm; by ~20% for 10 mm) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in full penetration) | Yes, progressed (more severe in full penetration) | Yes | |||||

| 20G | 95% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Tail | C6/7﹣C8/9 | - | 1﹣4/4﹣24 weeks | - | Decreased water, GAG and type I collagen expression | Decreased (by 25-75%) | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Open puncture | 3 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Posterial approach | L4/5 | - | 4/8 weeks | - | Altered collagens expression | - | - | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Open puncture | 3 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Posterior/anterior approach | L4/5 | - | 2/6 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | Yes (more significant for posterior puncture) | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Open puncture | 3 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C4/5, C8/9 | - | 2 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | Yes | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C5/6, C7/8 | - | 4 weeks | - | Altered collagens expression | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 21G | 85% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Tail | C4/5﹣C8/9 | - | 1﹣2/14﹣42 days | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 23G | 64% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Lateral approach | L5/6 | Repetitive puncture for five times | 1/2 weeks | - | - | - | - | - | Yes, increased neurons staining | |||||

| 27G | 51% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Dorsal approach | L4/5, L5/6 | - | 2/8 weeks | - | Altered collagens, SOX9, aggrecan expression | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | - | ||||||

| 31G | 26% | Percutaneous puncture | 1.5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C6/7 | - | 4 weeks | - | Altered collagens, aggrecan, MMP13, Adamts4 expression | - | - | - | ||||||

| 18G/22G | 128%/74% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Tail | C6/7, C8/9 | - | 2/4 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | - | - | |||||

| 18G/22G/26G | 128%/74%/20% | Percutaneous puncture | 2 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C6/7, C8/9 | - | 1/4 weeks | Altered creep behavior (for 18G) | - | Yes, degenerated (more severe for 18G) | Yes, progressed | - | ||||||

| 18/20/22G | 128%/95%/74% | Percutaneous puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C6/7, C8/9 | - | 2/8 weeks | - | Increased proteoglycan (for 18G, 20G) | Decreased (for 18G) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in 18G) | Yes, progressed (more severe in 18G) | ||||||

| 18/21/23/ 25/27/29G | 128%/85%/64%/ 53%/51%/36% | Percutaneous puncture | 5 cmm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | NA | - | 2/8﹣12 weeks | - | Altered collagens, SOX9, aggrecan expression | Decreased (by ~10% for 29/27/25G, by ~30% for 23/21G, by ~35% for 18G) | Yes, degenerated (more severe in 18G) | Yes, progressed (more severe in 18G) | ||||||

| 16G/18G/26G | 170%/128%/50% | Percutaneous puncture | Full penetration | Tail | C8/9 | - | 2/4 weeks | - | Altered Collagens expression | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in 16G, 18G) | Yes, progressed (more severe in 16G, 18G) | |||||||

| Mice | 26G | 100% | Percutaneous puncture | 2/3 of the disc thickness | Tail | C3/4﹣C6/7 | - | 4﹣8/4﹣32 weeks | - | Altered Collagens, MMPs, Adam8, Cxcl-1 expression | - | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | - | - | ||||

| 27G | 90% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Anterior approach | L3/4, L4/5 | - | 1/7 days | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | - | - | |||||

| 30G | 63% | Percutaneous puncture | Needle bevel completely inserted | Tail | NA | - | 14 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~25%) | Yes, degenerated | - | - | |||||

| 31G | 55% | Open puncture | 1 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Tail | C9/10 | - | 1/12 weeks | - | Altered collagens, GAG, aggrecan expression | Decreased (by ~30%) | Yes, degenerated | - | - | |||||

| 26G/29G | 100%/65% | Percutaneous puncture | 1.75 mm or 90% of the dorsoventral width | Dorsal approach | C6/7-C8/9 | - | 8 weeks | Decreased compressive stiffness, torsional stiffness, torque range, nc compressive ROM, increased creep displacement (for 26G) | Decreased GAG (by ~30% for 26G) | Decreased (by ~30% for 26G) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | - | - | |||||

| 27G/29G/31G | 90%/70%/55% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus/full penetration | Tail | C7/8, C9/10 | - | 4 weeks | - | - | NS | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (more severe in full penetration) | Yes, progressed (more severe in full penetration) | ||||||

| 27/30/33G | 90%/63%/40% | Open puncture | NA | Ventral approach | L4/5﹣L6/S1 | - | 1/8 weeks | - | Decreased GAG expression (for 27G and 30G) | Yes, degenerated (more severe for 27G and 30G) | - | |||||||

| 33G/35G | 50%/42% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Ventral/central/dorsal approach | L4/5 | - | 1/12 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated (more severe in central/dorsal approach) | Yes, progressed (more severe in central/dorsal approach) | ||||||

| Rabbit | 16G | 66% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Lateral approach | L2/3﹣L4/5 | NP removal with negative pressure | 6/12 weeks | - | Decreased collagen X expression | Decreased (by ~25%) | Yes, degenerated | - | - | ||||

| 16G | 66% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Posterolateral approach | L3/4, L5/6 | - | 4/12 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~45%) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 16G | 66% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterolateral approach | L2/3﹣L6/7 | NP removal with negative pressure | 2﹣8/12﹣24 weeks | Decreased ROM, increased creep displacement | Altered GAG, collagens, aggrecan, MMP3, SOX9 expression | Decreased (by ~25%) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 18G | 50% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterior/lateral approach | L2/3﹣L6/7 | NP removal with negative pressure | 1﹣4/4﹣14 weeks | - | Decreased GAG, proteoglycan (by ~30%) | Decreased (by ~30%) | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 18G | 50% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Lateral approach | L5/6 | NP removal with negative pressure | 1﹣4/4﹣12 weeks | - | Decreased GAG, collagens expression | Decreased (by ~50%) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 18G | 50% | Open puncture | 1 mm (superfical annulus defect); 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterior approach | L2/3﹣L4/5 | - | 2/12﹣24 weeks | - | - | Decreased (NS for 1 mm puncture, by ~25% for 5 mm puncture) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (for 5 mm puncture) | Yes, progressed (for 5 mm puncture) | ||||||

| 19G | 44% | Percutaneous puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Posterolateral approach | L2/3﹣L4/5 | NP removal with negative pressure | 9/20 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~40%) | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| 21G | 27% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterior approach | L3/4﹣L5/6 | NP removal with negative pressure | 4/12﹣28 weeks | - | Decreased proteoglycan expression | - | Yes, degenerated | - | - | |||||

| 16/18/21G | 66%/50%/27% | Open puncture | 5 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Anterior approach | L2/3﹣L5/6 | - | 4/8 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~30% for 16G, by ~10% for 18G/21G) | Yes, degenerated, NP herniation (for 16G/18G) | Yes, progressed (for 16G/18G) | ||||||

| Pig | 3.2 mm diameter trephine | 62% | Open puncture | NA | Anterolateral approach | NA | - | 8/39 weeks | - | - | Decreased (by ~15%) | Yes, degenerated | - | - | ||||

| 16G | 30% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Anterolateral approach | L2/5 | NP removal with negative pressure | 3/12﹣24 weeks | - | Altered Collagens, MMPs, aggrecan, TIMPs expression | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | ||||||

| 20G | 17% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | NA | L2/3, L4/5 | NP removal with negative pressure | 12/24 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | |||||

| Rhesus monkeys | 15G/20G | 41%/20% | Percutaneous puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Anterolateral approach | L1/2﹣L5/6 | - | 4/12 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated (more severe in 15G) | Yes, progressed (more severe in 15G) | |||||

| Ovine | 3.2-4.5 mm drill | 94﹣100% | Open puncture | 9﹣15 mm (through the annulus fibrosus) | Lateral approach | L1/2﹣L5/6 | - | 16 weeks | - | - | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | ||||

| CD-Canine | NA | 30﹣50% | Open puncture | Through the annulus fibrosus | Dorsal approach | L1/2, L3/4, L5/6 | - | 14 weeks | - | Altered aggrecan, collagens expression | - | Yes, degenerated | Yes, progressed | - | ||||

| Subtype | Method | Protocol | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Tactile responses | Rats are placed in individual plexiglass boxes on a stainless-steel mesh floor and are allowed to adjust for at least 20 minutes. | |

| A series of calibrated von Frey filaments (range 4﹣28 g) is applied perpendicularly to the plantar surface of a hindpaw with sufficient force to bend the filament for 6 seconds. | |||

| Brisk withdrawal or paw flinching is considered as a positive response. | |||

| Once a positive response is seen, the previous filament is applied. | |||

| If positive, the lower filament is determined to be the 50% paw-withdrawal threshold. | |||

| If negative, the next ascending filament is applied. | |||

| If that next filament provokes a positive response, the original filament is considered to be the 50% withdrawal threshold. | |||

| If the next ascending filament is negative, further ascending filaments are applied until a response is provoked. | |||

| Cautions: Avoid obscure foot pads and surgical incisions, and ensure that the position of the pain measurement is fixed in the central area of the foot; repeat the test four to five times at 5-min intervals on each animal. | |||

| Mechanical algesia | A von Frey anesthesiometer and rigid von Frey filaments are used to quantifying the withdrawal threshold of the hindpaw in response to mechanical stimulation. | ||

| Rats are placed in individual plexiglass boxes on a stainless-steel mesh floor and are allowed to acclimate for at least 20 minutes. | |||

| A 0.5-mm diameter polypropylene rigid tip is used to apply a force to the plantar surface of the hindpaw. | |||

| The force causing the withdrawal response is recorded by the anesthesiometer. | |||

| The anesthesiometer is calibrated before each recording. | |||

| The test is repeated four to five times at 5-minute intervals on each animal, and the mean value is calculated. | |||

| Mechanical hyperalgesia/pressure hyperalgesia | The vocalization threshold based on the force of an applied force gauge is measured by pressing the 0.5-c | ||

| The force was slowly increased 100 g/s until an audible vocalization is heard. | |||

| A cut off force of 1000 g is used to prevent tissue trauma. | |||

| The tests should be carried out in duplicate, and the mean value is taken as the nociceptive threshold. | |||

| Caution: Postoperative testing should be delayed until one week after surgery to allow the abdominal tissue to heal. | |||

| Thermal | Hot algesia (plate) | Rats were placed within a plexiglass chamber on a transparent glass surface and allowed to acclimate for at least 20 minutes. | |

| A thermal stimulation meter is used with the temperature set to 50°C and the stimulating time set to 30 seconds. | |||

| Brisk withdrawal or paw flinching is considered as a positive response. | |||

| The duration from stimulation to positive responses is recorded and noted as paw withdrawal latency. | |||

| Individual measurements were repeated four to five times. The intermittent period for repetitive measurements of each rat is 15 minutes. | |||

| The mean value was calculated as the thermal threshold. | |||

| Cautions: The tests should be restricted to a certain period in a day, like 8-12 a.m., to avoid the influence of memorial reflex. Data from scalded rats should be eliminated to avoid bias. | |||

| Hot algesia (tail flick test) | Animal are calmed by enclosing their heads with a towel on the apparatus, and acclimate to the test environment for 30 minutes. | ||

| Radiant heat is applied to the tail 5 cm from the tip using a tail-fick analgesia meter. | |||

| Record baseline latencies of the animals. Test the animals’ tail-flick response using a tail-flick apparatus, and adjust the intensity of the heat source to produce tail-flick latencies of 3 to 4 seconds. For mice, focus the light beam ~15 mm from the tip of the tail. For rats, stimulate an area ~50 mm from the tip of the tail. In the absence of a withdrawal reflex, set the stimulus cutoff to 10 seconds to avoid possible tissue damage. | |||

| Record the time for the animal to show a tail-flick response, or assign a value of 10 seconds (cutoff time) if no tail-flick is observed. | |||

| After sufficient data collection (n = 8 per group and dose), perform statistical analysis and calculate the means and standard errors for data presentation. | |||

| Cold algesia (hindpaw and back) | The total duration of acetone-evoked behaviours (e.g. flinching, licking or biting) are measured in seconds for 1 minute after a drop of acetone (25 μL) is applied to the plantar surface of the hindpaw using a blunt needle connected to a 1 mL-syringe. | ||

| Increased behavioural response to acetone suggests the development of cold hypersensitivity. | |||

| The grades are recorded as follow: 0, static; 1, slow flinching or paw movement; 2, fast flinching with paw shaking; 3, fast flinching, biting and paw remaining off the ground. | |||

| Cold algesia (tail) | Animals were placed individually in the test chamber for 60 minutes prior to testing. | ||

| Half of the length of the tail was dipped into the cold water, and the latency to tail withdrawal was measured. | |||

| A maximum cut-off of 30 seconds was set to avoid tissue damage. |

Additional Table 4 Stimuli-evoked hypersensitivity measurement in rodent model

| Subtype | Method | Protocol | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Tactile responses | Rats are placed in individual plexiglass boxes on a stainless-steel mesh floor and are allowed to adjust for at least 20 minutes. | |

| A series of calibrated von Frey filaments (range 4﹣28 g) is applied perpendicularly to the plantar surface of a hindpaw with sufficient force to bend the filament for 6 seconds. | |||

| Brisk withdrawal or paw flinching is considered as a positive response. | |||

| Once a positive response is seen, the previous filament is applied. | |||

| If positive, the lower filament is determined to be the 50% paw-withdrawal threshold. | |||

| If negative, the next ascending filament is applied. | |||

| If that next filament provokes a positive response, the original filament is considered to be the 50% withdrawal threshold. | |||

| If the next ascending filament is negative, further ascending filaments are applied until a response is provoked. | |||

| Cautions: Avoid obscure foot pads and surgical incisions, and ensure that the position of the pain measurement is fixed in the central area of the foot; repeat the test four to five times at 5-min intervals on each animal. | |||

| Mechanical algesia | A von Frey anesthesiometer and rigid von Frey filaments are used to quantifying the withdrawal threshold of the hindpaw in response to mechanical stimulation. | ||

| Rats are placed in individual plexiglass boxes on a stainless-steel mesh floor and are allowed to acclimate for at least 20 minutes. | |||

| A 0.5-mm diameter polypropylene rigid tip is used to apply a force to the plantar surface of the hindpaw. | |||

| The force causing the withdrawal response is recorded by the anesthesiometer. | |||

| The anesthesiometer is calibrated before each recording. | |||

| The test is repeated four to five times at 5-minute intervals on each animal, and the mean value is calculated. | |||

| Mechanical hyperalgesia/pressure hyperalgesia | The vocalization threshold based on the force of an applied force gauge is measured by pressing the 0.5-c | ||

| The force was slowly increased 100 g/s until an audible vocalization is heard. | |||

| A cut off force of 1000 g is used to prevent tissue trauma. | |||

| The tests should be carried out in duplicate, and the mean value is taken as the nociceptive threshold. | |||

| Caution: Postoperative testing should be delayed until one week after surgery to allow the abdominal tissue to heal. | |||

| Thermal | Hot algesia (plate) | Rats were placed within a plexiglass chamber on a transparent glass surface and allowed to acclimate for at least 20 minutes. | |

| A thermal stimulation meter is used with the temperature set to 50°C and the stimulating time set to 30 seconds. | |||

| Brisk withdrawal or paw flinching is considered as a positive response. | |||

| The duration from stimulation to positive responses is recorded and noted as paw withdrawal latency. | |||

| Individual measurements were repeated four to five times. The intermittent period for repetitive measurements of each rat is 15 minutes. | |||

| The mean value was calculated as the thermal threshold. | |||

| Cautions: The tests should be restricted to a certain period in a day, like 8-12 a.m., to avoid the influence of memorial reflex. Data from scalded rats should be eliminated to avoid bias. | |||

| Hot algesia (tail flick test) | Animal are calmed by enclosing their heads with a towel on the apparatus, and acclimate to the test environment for 30 minutes. | ||

| Radiant heat is applied to the tail 5 cm from the tip using a tail-fick analgesia meter. | |||

| Record baseline latencies of the animals. Test the animals’ tail-flick response using a tail-flick apparatus, and adjust the intensity of the heat source to produce tail-flick latencies of 3 to 4 seconds. For mice, focus the light beam ~15 mm from the tip of the tail. For rats, stimulate an area ~50 mm from the tip of the tail. In the absence of a withdrawal reflex, set the stimulus cutoff to 10 seconds to avoid possible tissue damage. | |||

| Record the time for the animal to show a tail-flick response, or assign a value of 10 seconds (cutoff time) if no tail-flick is observed. | |||

| After sufficient data collection (n = 8 per group and dose), perform statistical analysis and calculate the means and standard errors for data presentation. | |||

| Cold algesia (hindpaw and back) | The total duration of acetone-evoked behaviours (e.g. flinching, licking or biting) are measured in seconds for 1 minute after a drop of acetone (25 μL) is applied to the plantar surface of the hindpaw using a blunt needle connected to a 1 mL-syringe. | ||

| Increased behavioural response to acetone suggests the development of cold hypersensitivity. | |||

| The grades are recorded as follow: 0, static; 1, slow flinching or paw movement; 2, fast flinching with paw shaking; 3, fast flinching, biting and paw remaining off the ground. | |||

| Cold algesia (tail) | Animals were placed individually in the test chamber for 60 minutes prior to testing. | ||

| Half of the length of the tail was dipped into the cold water, and the latency to tail withdrawal was measured. | |||

| A maximum cut-off of 30 seconds was set to avoid tissue damage. |

| Method | Protocol | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Grip Force assay | The mice grip a metal bar attached to a Grip Strength Meter (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, USA) with their forepaws. | |

| The mice are slowly pulled back by the tail, exerting a stretching force. | ||

| The peak force in grams at the point of release is recorded twice at a 10 minutes interval. | ||

| A decrease in grip force is interpreted as a measure of hypersensitivity to axial stretching. | ||

| Tail suspension | Mice are suspended individually underneath a platform by the tail with adhesive tape attached 0.5 to 1 cm from the base of the tail and are videotaped for 180 seconds. | |

| The duration of time spent in (a) immobility (not moving but stretched out) and (b) escape behaviours (rearing to reach the underside of the platform, extending to reach the floor, or self-supported at the base of the tail or the suspension tape) are determined. | ||

| The duration of immobility reflects the animal’s willingness to stretch its main body axis. | ||

| Deceased immobility is indicative of axial discomfort. | ||

| FlexMaze assay | The FlexMaze apparatus consists of a long (8 cm × 80 cm) transparent corridor with regularly spaced staggered doors and neutral (beige) 15 cm × 15 cm compartments with 6 cm × 6 cm openings on either side | |

| The FlexMaze apparatus is placed in a quiet room illuminated with white light. | ||

| Mice are placed into one of the neutral compartments and are allowed to explore the apparatus freely for 10 minutes. | ||

| Videotapes are analyzed for total distance covered and average velocity. |

Additional Table 5 Movement-evoked hypersensitivity measurement in rodent model

| Method | Protocol | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Grip Force assay | The mice grip a metal bar attached to a Grip Strength Meter (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, USA) with their forepaws. | |

| The mice are slowly pulled back by the tail, exerting a stretching force. | ||

| The peak force in grams at the point of release is recorded twice at a 10 minutes interval. | ||

| A decrease in grip force is interpreted as a measure of hypersensitivity to axial stretching. | ||

| Tail suspension | Mice are suspended individually underneath a platform by the tail with adhesive tape attached 0.5 to 1 cm from the base of the tail and are videotaped for 180 seconds. | |

| The duration of time spent in (a) immobility (not moving but stretched out) and (b) escape behaviours (rearing to reach the underside of the platform, extending to reach the floor, or self-supported at the base of the tail or the suspension tape) are determined. | ||

| The duration of immobility reflects the animal’s willingness to stretch its main body axis. | ||

| Deceased immobility is indicative of axial discomfort. | ||

| FlexMaze assay | The FlexMaze apparatus consists of a long (8 cm × 80 cm) transparent corridor with regularly spaced staggered doors and neutral (beige) 15 cm × 15 cm compartments with 6 cm × 6 cm openings on either side | |

| The FlexMaze apparatus is placed in a quiet room illuminated with white light. | ||

| Mice are placed into one of the neutral compartments and are allowed to explore the apparatus freely for 10 minutes. | ||

| Videotapes are analyzed for total distance covered and average velocity. |

| Grade | Structure | Distinction of nucleus and annulus | Signal intensity | Height of intervertebral disc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Homogeneous, bright white | Clear | Hyperintense, isointense to cerebrospinal fluid | Normal |

| II | Inhomogeneous with or without horizontal bands | Clear | Hyperintense, isointense to cerebrospinal fluid | Normal |

| III | Inhomogeneous, gray | Unclear | Intermediate | Normal to slightly decreased |

| IV | Inhomogeneous, gray to black | Lost | Intermediate to hypointense | Normal to moderately decreased |

| V | Inhomogeneous, black | Lost | Hypointense | Collapsed disc space |

Additional Table 6 Pfirrmann et al.’s classification of disc degeneration

| Grade | Structure | Distinction of nucleus and annulus | Signal intensity | Height of intervertebral disc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Homogeneous, bright white | Clear | Hyperintense, isointense to cerebrospinal fluid | Normal |

| II | Inhomogeneous with or without horizontal bands | Clear | Hyperintense, isointense to cerebrospinal fluid | Normal |

| III | Inhomogeneous, gray | Unclear | Intermediate | Normal to slightly decreased |

| IV | Inhomogeneous, gray to black | Lost | Intermediate to hypointense | Normal to moderately decreased |

| V | Inhomogeneous, black | Lost | Hypointense | Collapsed disc space |

| Grade | Annulus fibrosus | Nucleus pulposus |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal structure | Normal structure |

| 1 | Mildly serpentine appearance of the annulus fibrosus | No proliferative connective tissue but a honey-comb appearance of the extracellular matrix |

| 2 | Moderately serpentine appearance of the annulus fibrosus with rupture | As much as 24% of the nucleus pulposus occupied by proliferative connective tissue |

| 3 | Severely serpentine appearance of the annulus fibrosus with mildly reversed contour | 25% to 50% of the nucleus pulposus occupied by proliferative connective tissue |

| 4 | Severely reversed contour | More than 50% occupied by proliferative connective tissue |

| 5 | Indistinct | Complete replacement of normal architecture by proliferative connective tissue |

Additional Table 7 Nomura et al.’s histological grading system

| Grade | Annulus fibrosus | Nucleus pulposus |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal structure | Normal structure |

| 1 | Mildly serpentine appearance of the annulus fibrosus | No proliferative connective tissue but a honey-comb appearance of the extracellular matrix |

| 2 | Moderately serpentine appearance of the annulus fibrosus with rupture | As much as 24% of the nucleus pulposus occupied by proliferative connective tissue |

| 3 | Severely serpentine appearance of the annulus fibrosus with mildly reversed contour | 25% to 50% of the nucleus pulposus occupied by proliferative connective tissue |

| 4 | Severely reversed contour | More than 50% occupied by proliferative connective tissue |

| 5 | Indistinct | Complete replacement of normal architecture by proliferative connective tissue |

| Grade | Structure | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| I | Annulus fibrosus | 1. Normal pattern of fibrocartilage lamellae (U-shaped in the posterior aspect and slightly convex in the anterior aspect), without ruptured fibers and a serpentine appearance anywhere within the annulus |

| 2. Ruptured or serpentine patterned fibers in less than 30% of the annulus | ||

| 3. Ruptured or serpentine patterned fibers in more than 30% of the annulus | ||

| II | Border between the annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal |

| 2. Minimal interruption | ||

| 3. Moderate or severe interruption | ||

| III | Cellularity of the nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal cellularity with large vacuoles in the gelatinous structure of the matrix |

| 2. Slight decrease in the number of cells and fewer vacuoles | ||

| 3. Moderate/severe decrease (> 50%) in the number of cells and no vacuoles | ||

| IV | Morphology of the nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal gelatinous appearance |

| 2. Slight condensation of the extracellular matrix | ||

| 3. Moderate/severe condensation of the extracellular matrix |

Additional Table 8 Masuda et al.’s histological grading scale

| Grade | Structure | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| I | Annulus fibrosus | 1. Normal pattern of fibrocartilage lamellae (U-shaped in the posterior aspect and slightly convex in the anterior aspect), without ruptured fibers and a serpentine appearance anywhere within the annulus |

| 2. Ruptured or serpentine patterned fibers in less than 30% of the annulus | ||

| 3. Ruptured or serpentine patterned fibers in more than 30% of the annulus | ||

| II | Border between the annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal |

| 2. Minimal interruption | ||

| 3. Moderate or severe interruption | ||

| III | Cellularity of the nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal cellularity with large vacuoles in the gelatinous structure of the matrix |

| 2. Slight decrease in the number of cells and fewer vacuoles | ||

| 3. Moderate/severe decrease (> 50%) in the number of cells and no vacuoles | ||

| IV | Morphology of the nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal gelatinous appearance |

| 2. Slight condensation of the extracellular matrix | ||

| 3. Moderate/severe condensation of the extracellular matrix |

| Grade | Structure | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| I | Cellularity of the annulus fibrosus | 1. Fibroblasts comprise more than 75% of the cells |

| 2. Neither fibroblasts nor chondrocytes comprise more than 75% of the cells | ||

| 3. Chondrocytes comprise more than 75% of the cells | ||

| II | Morphology of the annulus fibrosus | 1. Well-organized collagen lamellae without ruptured or serpentine fibers |

| 2. Inward bulging, ruptured or serpentine fibers in less than one-third of the annulus | ||

| 3. Inward bulging, ruptured or serpentine fibers in more than one-third of the annulus | ||

| III | Border between the annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal, without any interruption |

| 2. Minimal interruption | ||

| 3. Moderate or severe interruption | ||

| IV | Cellularity of the nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal cellularity with stellar shaped nuclear cells evenly distributed throughout the nucleus |

| 2. Slight decrease in the number of cells with some clustering | ||

| 3. Moderate or severe decrease (> 50%) in the number of cells with all remaining cells clustered and separated by dense areas of proteoglycans | ||

| V | Morphology of the nucleus pulposus | 1. Round, comprising at least half of the disc area in midsagittal sections |

| 2. Rounded or irregularly shaped, comprising one-quarter to half of the disc area in midsagittal sections | ||

| 3. Irregularly shaped, comprising less than one-quarter of the disc area in midsagittal sections |

Additional Table 9 Han et al.’s histological grading scale

| Grade | Structure | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| I | Cellularity of the annulus fibrosus | 1. Fibroblasts comprise more than 75% of the cells |

| 2. Neither fibroblasts nor chondrocytes comprise more than 75% of the cells | ||

| 3. Chondrocytes comprise more than 75% of the cells | ||

| II | Morphology of the annulus fibrosus | 1. Well-organized collagen lamellae without ruptured or serpentine fibers |

| 2. Inward bulging, ruptured or serpentine fibers in less than one-third of the annulus | ||

| 3. Inward bulging, ruptured or serpentine fibers in more than one-third of the annulus | ||

| III | Border between the annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal, without any interruption |

| 2. Minimal interruption | ||

| 3. Moderate or severe interruption | ||

| IV | Cellularity of the nucleus pulposus | 1. Normal cellularity with stellar shaped nuclear cells evenly distributed throughout the nucleus |

| 2. Slight decrease in the number of cells with some clustering | ||

| 3. Moderate or severe decrease (> 50%) in the number of cells with all remaining cells clustered and separated by dense areas of proteoglycans | ||

| V | Morphology of the nucleus pulposus | 1. Round, comprising at least half of the disc area in midsagittal sections |

| 2. Rounded or irregularly shaped, comprising one-quarter to half of the disc area in midsagittal sections | ||

| 3. Irregularly shaped, comprising less than one-quarter of the disc area in midsagittal sections |

| Grade | Nucleus | Annulus | Endplate | Vertebral body |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Bulging gel | Annulus | Hyaline, uniformly thick | Margins rounded |

| II | White fibrous tissue peripherally | Discrete fibrosus lamellas | Thickness irregular | Margins pointed |

| III | Consolidated fibrous tissue | Mucinous material between lamellas | Focal defects in cartilage | Early chondrophytes or osteophytes at margins |

| IV | Horizontal clefts parallel to endplate | Extensive mucinous infiltration; loss of annular-nuclear demarcation | Fibrocartilage extending from subchondral bone; irregularity and focal sclerosis in subchondral bone | Osteophytes less than 2 mm |

| V | Clefts extend through nucleus and annulus | Focal disruptions | Diffuse sclerosis | Osteophytes greater than 2 mm |

Additional Table 10. Thompson et al.’s description of morphologic grades

| Grade | Nucleus | Annulus | Endplate | Vertebral body |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Bulging gel | Annulus | Hyaline, uniformly thick | Margins rounded |

| II | White fibrous tissue peripherally | Discrete fibrosus lamellas | Thickness irregular | Margins pointed |

| III | Consolidated fibrous tissue | Mucinous material between lamellas | Focal defects in cartilage | Early chondrophytes or osteophytes at margins |

| IV | Horizontal clefts parallel to endplate | Extensive mucinous infiltration; loss of annular-nuclear demarcation | Fibrocartilage extending from subchondral bone; irregularity and focal sclerosis in subchondral bone | Osteophytes less than 2 mm |

| V | Clefts extend through nucleus and annulus | Focal disruptions | Diffuse sclerosis | Osteophytes greater than 2 mm |

| Global disc appearance | Grade |

|---|---|

| Macroscopic assessment IVD, endplate, and adjacent bone) | Grade 1 = normal juvenile disc; Grade 2 = normal adult disc; Grade 3 = mild disc degeneration; Grade 4 = moderate disc degeneration; Grade 5 = severe disc degeneration |

| IVD | |

| Cells (chondrocyte proliferation) | 0 = no proliferation; 1 = increased cell density; 2 = connection of two chondrocytes; 3 = small size clones (several chondrocytes, grouped together, 3﹣7 cells); 4 = moderate size clones (8﹣15 cells); 5 = huge clones (> 15 cells) |

| Multiple chondrocytes growing in small, rounded groups or clusters sharply demarcated by a rim of territorial matrix | |

| Granular changes | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Eosinophilic-staining amorphous granules within the fibrocartilage matrix | |

| Mucous degeneration | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Cystic, oval, or irregular areas with an intense deposition of acid mucopolysaccharides (i.e., sulfated glycosaminoglycans) staining dark blue with Alcian blue/PAS | |

| Edge neovascularity | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Newly formed blood vessels with reparative alteration | |

| Rim lesions | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Radial tears adjacent to the endplates | |

| Concentric tears | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Tears after the orientation of collagen fiber bundles in the annulus fibrosus | |

| Radial tears | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Radiating defects extending from the nucleus pulposus to the outer annulus lamellae parallel or oblique to the endplate (clefts) | |

| Notochordal cells | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Embryonic disc cells | |

| Cell death | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Altered phenotype | |

| Scar formation | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Amorphous fibrosus tissue without any differentiation | |

| Tissue defects | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Voids within the tissue (e.g., resulting from tissue resorption, probably filled with fluid in vivo) | |

| Endplate | |

| Cells | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Number of cells (chondrocyte clusters) | |

| Structural disorganization | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Focal disorganization of the cartilaginous matrix with clumping of chondrocytes | |

| Clefts | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Tears in the endplate | |

| Microfracture | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Disruption of the subchondral bone | |

| Neovascularization | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Vessels penetrating from the bone marrow into the endplate in conjunction with microfractures | |

| New bone formation | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Bone islands within the cartilage | |

| Bony sclerosis | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Formation of new bone | |

| Physiologic vessels | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Obliterated vessels | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Scar formation | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Amorphous fibrosus tissue without any differentiation | |

| Tissue defects | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Voids within the tissue (e.g., resulting from tissue resorption, probably filled with fluid in vivo) |

Additional Table 11. Boos et al.’s variables of macroscopic and histological assessment

| Global disc appearance | Grade |

|---|---|

| Macroscopic assessment IVD, endplate, and adjacent bone) | Grade 1 = normal juvenile disc; Grade 2 = normal adult disc; Grade 3 = mild disc degeneration; Grade 4 = moderate disc degeneration; Grade 5 = severe disc degeneration |

| IVD | |

| Cells (chondrocyte proliferation) | 0 = no proliferation; 1 = increased cell density; 2 = connection of two chondrocytes; 3 = small size clones (several chondrocytes, grouped together, 3﹣7 cells); 4 = moderate size clones (8﹣15 cells); 5 = huge clones (> 15 cells) |

| Multiple chondrocytes growing in small, rounded groups or clusters sharply demarcated by a rim of territorial matrix | |

| Granular changes | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Eosinophilic-staining amorphous granules within the fibrocartilage matrix | |

| Mucous degeneration | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Cystic, oval, or irregular areas with an intense deposition of acid mucopolysaccharides (i.e., sulfated glycosaminoglycans) staining dark blue with Alcian blue/PAS | |

| Edge neovascularity | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Newly formed blood vessels with reparative alteration | |

| Rim lesions | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Radial tears adjacent to the endplates | |

| Concentric tears | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Tears after the orientation of collagen fiber bundles in the annulus fibrosus | |

| Radial tears | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Radiating defects extending from the nucleus pulposus to the outer annulus lamellae parallel or oblique to the endplate (clefts) | |

| Notochordal cells | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Embryonic disc cells | |

| Cell death | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Altered phenotype | |

| Scar formation | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Amorphous fibrosus tissue without any differentiation | |

| Tissue defects | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Voids within the tissue (e.g., resulting from tissue resorption, probably filled with fluid in vivo) | |

| Endplate | |

| Cells | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Number of cells (chondrocyte clusters) | |

| Structural disorganization | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Focal disorganization of the cartilaginous matrix with clumping of chondrocytes | |

| Clefts | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Tears in the endplate | |

| Microfracture | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Disruption of the subchondral bone | |

| Neovascularization | 0 = absent; 1 = rarely present; 2 = present in intermediate amounts of 1 to 3; 3 = abundantly present |

| Vessels penetrating from the bone marrow into the endplate in conjunction with microfractures | |

| New bone formation | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Bone islands within the cartilage | |

| Bony sclerosis | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Formation of new bone | |

| Physiologic vessels | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Obliterated vessels | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Scar formation | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Amorphous fibrosus tissue without any differentiation | |

| Tissue defects | 0 = absent; 1 = present |

| Voids within the tissue (e.g., resulting from tissue resorption, probably filled with fluid in vivo) |

| Criteria | Range |

|---|---|

| Intervertebral disc region | |

| Chondrocyte proliferation/density | 0﹣6 |

| Mucous degeneration | 0﹣4 |

| Cell death | 0﹣4 |

| Tear/cleft formation | 0﹣4 |

| Granular changes | 0﹣4 |

| Vertebral endplate region | |

| Cell proliferation | 0﹣4 |

| Cartilage disorganization | 0﹣4 |

| Cartilage cracks | 0﹣4 |

| Microfracture | 0﹣2 |

| New bone formation | 0﹣2 |

| Bony sclerosis | 0﹣2 |

Additional Table 12. Boyd et al.’s grading for intervertebral disc and endplate regions

| Criteria | Range |

|---|---|

| Intervertebral disc region | |

| Chondrocyte proliferation/density | 0﹣6 |

| Mucous degeneration | 0﹣4 |

| Cell death | 0﹣4 |

| Tear/cleft formation | 0﹣4 |

| Granular changes | 0﹣4 |

| Vertebral endplate region | |

| Cell proliferation | 0﹣4 |

| Cartilage disorganization | 0﹣4 |

| Cartilage cracks | 0﹣4 |

| Microfracture | 0﹣2 |

| New bone formation | 0﹣2 |

| Bony sclerosis | 0﹣2 |

| Method | Protocol | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | ASTM F2256-05 (T-Peel by Tension Loading) | At least 10 specimens of each type are to be tested. | |

| Tissue specimen thickness should be uniform and less than 5 mm. | |||

| The specimen width is 2.5 ± 0.1 cm, and the specimen length is 15 ± 0.2 cm (2.5 cm unbonded, 12.5 cm bonded). | |||

| A bond force of 5﹣10 N is applied until the experimental adhesive sets. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| The sample apparatus is loaded into the tensile test machine and at a constant cross-head speed of 250 mm/min. | |||

| The load as a function of displacement and the type of failure (percentage cohesive, adhesive, or substrate failure) are recorded | |||

| ASTM F2258-05 (Tension) | At least ten specimens of each type are to be tested. | ||

| The bond area of 2.5 ± 0.005 cm by 2.5 ± 0.005 cm. | |||

| A bond force of 1﹣2 N is applied until the experimental adhesive sets. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| The sample apparatus is loaded into the tensile test machine and at a constant cross-head speed of 2 mm/min. | |||

| The load at failure (maximum load sustained) and the type of failure (percentage cohesive, adhesive, or substrate failure) are recorded. | |||

| ASTM F2255-05 (Lap-Shear by Tension Loading) | At least 10 specimens of each type are to be tested. | ||

| The length of the tissue substrate attached to each specimen holder should be 1.5 times the length of the bond area (1.0 ± 0.1 cm). | |||

| The tissue specimens should be 1﹣2 mm thick. | |||

| A bond force of 1﹣2 N is placed on the bond area between the two tissue specimens (1.0 ± 0.1 cm by 2.5 ± 0.1 cm) until the experimental adhesive sets. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| The sample is loaded into the testing apparatus such that the load coincides with the long axis of the sample. | |||

| The sample is loaded to failure at a constant crosshead speed of 5 mm/min. The load at failure (maximum load sustained) and the type of failure (percentage cohesive, adhesive, or substrate failure) are recorded. | |||

| ASTM F2458-05 (Wound Closure Strength of Tissue Adhesives and Sealants) | At least ten specimens of each type are to be tested. | ||

| Two tissue samples of identical size (10 ± 0.2 cm by 2.5 ± 0.1 cm) are bonded using the experimental adhesive on the 2.5 cm side, with a bonding length of 0.5 cm on either side of the join line. | |||

| The thickness of the specimens should be uniform and less than 5 mm. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| The sample is loaded into the testing apparatus such that the load coincides with the long axis of the sample. | |||

| The distance from the grip to the midline of each sample is 5 cm, with the remaining 5 cm held between the grips. | |||

| The specimen is loaded to failure at a constant speed of 50 mm/min. | |||

| The time from application to testing (cure time), force at failure (maximum force required to disrupt substrate), and the type of failure (percentage cohesive, adhesive, or substrate failure) are recorded. | |||

| ASTM F2392-04 (Burst Strength of Surgical Sealants) | At least 10 specimens of each type are to be tested. | ||

| This test employs an apparatus that clamps down on a substrate to prevent leakage. | |||

| The thickness of the tissue should be uniform and not exceed 5 mm. | |||

| Tissue samples should be circles 3.0 ± 0.1 cm in diameter, in which a 3.0 mm diameter hole is created using a biopsy punch. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| This test uses a stationary fixture containing test substrate and the sealant to be tested. | |||

| A 1.0 mm thick PTFE mask with a 15 mm diameter hole is secured over the sample, with the hole in the mask centered with the hole in the sample. | |||

| Saline is pumped into the fixture at a constant rate of 2 mL/min, and pressures are measured at all time points. | |||

| Peak pressure and failure type (cohesive, adhesive, or substrate) are recorded. | |||

| Ex vivo (risk of herniation) | Ramp-to-Failure Testing | Herniation risk was evaluated through failure testing using a MTS Bionix Servohydraulic Test System (MTS, Eden Parairie, MN, USA). | |

| Specimens were placed on the MTS stage at an offset of 5° from the normal axis, with the postero-lateral portion of the disc at the outside of the bend to simulate postero-lateral flexion. | |||

| A force of ~20 N was applied as a pre-load. | |||

| The samples were then compressed in displacement-control mode using a ramp function at 2 mm/min until failure. | |||

| Biomechanical output measures that quantitatively describe IVD herniation risk include failure strength, failure strain, subsidence-to-failure, maximum stiffness, work-to-failure, yield strength, ultimate strength, and the ratios of the ultimate or yield strength to the failure strength of the motion segment. | |||

| Fatigue Endurance Testing | The fatigue loading protocol consisted of cyclic eccentric compression between 50 N and 300 N at 1 Hz and at an offset of 20 mm to induce a physiological bending moment of 6 N·m. | ||

| The loading indenter cyclically rotated from -135° to +135° from the axis opposite of the incision site at 15° increments with 1 minute of cyclic loading at each location. | |||

| This test setup was considered to mimic the “worst-case scenario” as loading opposite of the injury site was expected to aggravate NP extrusion. | |||

| Failure was defined by significant NP protrusion greater than 2 mm. | |||

| The main outcome measure from the fatigue tests was cycles-to-failure, which was indicative of fatigue endurance. |

Additional Table 13. Methods for the evaluation of adhesive properties

| Method | Protocol | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | ASTM F2256-05 (T-Peel by Tension Loading) | At least 10 specimens of each type are to be tested. | |

| Tissue specimen thickness should be uniform and less than 5 mm. | |||

| The specimen width is 2.5 ± 0.1 cm, and the specimen length is 15 ± 0.2 cm (2.5 cm unbonded, 12.5 cm bonded). | |||

| A bond force of 5﹣10 N is applied until the experimental adhesive sets. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| The sample apparatus is loaded into the tensile test machine and at a constant cross-head speed of 250 mm/min. | |||

| The load as a function of displacement and the type of failure (percentage cohesive, adhesive, or substrate failure) are recorded | |||

| ASTM F2258-05 (Tension) | At least ten specimens of each type are to be tested. | ||

| The bond area of 2.5 ± 0.005 cm by 2.5 ± 0.005 cm. | |||

| A bond force of 1﹣2 N is applied until the experimental adhesive sets. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| The sample apparatus is loaded into the tensile test machine and at a constant cross-head speed of 2 mm/min. | |||

| The load at failure (maximum load sustained) and the type of failure (percentage cohesive, adhesive, or substrate failure) are recorded. | |||

| ASTM F2255-05 (Lap-Shear by Tension Loading) | At least 10 specimens of each type are to be tested. | ||

| The length of the tissue substrate attached to each specimen holder should be 1.5 times the length of the bond area (1.0 ± 0.1 cm). | |||

| The tissue specimens should be 1﹣2 mm thick. | |||

| A bond force of 1﹣2 N is placed on the bond area between the two tissue specimens (1.0 ± 0.1 cm by 2.5 ± 0.1 cm) until the experimental adhesive sets. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| The sample is loaded into the testing apparatus such that the load coincides with the long axis of the sample. | |||

| The sample is loaded to failure at a constant crosshead speed of 5 mm/min. The load at failure (maximum load sustained) and the type of failure (percentage cohesive, adhesive, or substrate failure) are recorded. | |||

| ASTM F2458-05 (Wound Closure Strength of Tissue Adhesives and Sealants) | At least ten specimens of each type are to be tested. | ||

| Two tissue samples of identical size (10 ± 0.2 cm by 2.5 ± 0.1 cm) are bonded using the experimental adhesive on the 2.5 cm side, with a bonding length of 0.5 cm on either side of the join line. | |||

| The thickness of the specimens should be uniform and less than 5 mm. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| The sample is loaded into the testing apparatus such that the load coincides with the long axis of the sample. | |||

| The distance from the grip to the midline of each sample is 5 cm, with the remaining 5 cm held between the grips. | |||

| The specimen is loaded to failure at a constant speed of 50 mm/min. | |||

| The time from application to testing (cure time), force at failure (maximum force required to disrupt substrate), and the type of failure (percentage cohesive, adhesive, or substrate failure) are recorded. | |||

| ASTM F2392-04 (Burst Strength of Surgical Sealants) | At least 10 specimens of each type are to be tested. | ||

| This test employs an apparatus that clamps down on a substrate to prevent leakage. | |||

| The thickness of the tissue should be uniform and not exceed 5 mm. | |||

| Tissue samples should be circles 3.0 ± 0.1 cm in diameter, in which a 3.0 mm diameter hole is created using a biopsy punch. | |||

| The specimens are conditioned for 1 hour ± 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline at 37 ± 1°C. | |||

| After conditioning, samples are acclimated to the test temperature for 15 minutes. | |||

| This test uses a stationary fixture containing test substrate and the sealant to be tested. | |||

| A 1.0 mm thick PTFE mask with a 15 mm diameter hole is secured over the sample, with the hole in the mask centered with the hole in the sample. | |||

| Saline is pumped into the fixture at a constant rate of 2 mL/min, and pressures are measured at all time points. | |||